|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 22 - Original copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

ADDENDUM: I AM STILL WORKING ON THIS POST

oapy Smith's "STAR" notebook, 1883-84, St. Louis, San Francisco, Soapy arrested: Pages #22-23

This post is on page 22 and 23 of the "STAR" notebook. I am combining these two pages as they only account for a total of seven lines. They are not appearing to be a continuation of earlier pages, but appear to be notes Soapy made as two separate, stand-alone notations. Page 22 is not dated. Page 23 is dated twice, December 31, 1883 and January 2, 1884.

This is the continuation of deciphering Soapy Smith's "star" notebook from the Geri Murphy collection. A complete introduction to this notebook can be seen on

page 1. These notebook pages have never been published before! They continue to be of revealing interest. The picture that these pages draw is of young 23 year-old Jefferson pursuing "soap sales" over a very wide spread of territory and in a very tenacious, even driven, way.

The notebook(s) are in Soapy's handwriting, and sometimes pretty hard to decipher. A large part of this series of posts is to transcribe the pages, one-at-a-time, and receive help from readers on identifying words I am having trouble with, as well as correcting any of my deciphered words. My long time friend, and publisher, Art Petersen, has been a great help in deciphering and adding additional information.

I will include the original copy, an enhanced copy, and a negative copy of each page. Also included will be a copy with typed out text, as tools to aid in deciphering the notes.

PAGE 22:

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 22 - Enhanced copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

There are a total of 24 pages. This means that there may be upwards of 24 individuals posts for this one notebook. Links to the past and future pages (pages 1, 2, 3, etc.) are added at the bottom of each post for ease of research. When completed there will be a sourced partial record of Soapy's activities and whereabouts for 1882-1884.

Important to note that the pages of the notebook do not appear to be in chronological order, with Soapy making additional notes on a town and topic several pages later.

Although the communication of twenty-three-year-old Jefferson Randolph Smith II is with himself, the writing also communicates with us about him 142 years later (and potentially far beyond today).

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 22 - Negative copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 22 - Deciphered copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy

|

(Click image to enlarge)

The date of this notation is unknown, though it is probably not too far from the dates noted in page 20-21 (1883-1884).

- Line 1: "W. O. Monroe:" I could not find anything in the St. Louis newspapers for 1883-84 in regards to “W. O. Monroe,” but I did find a "William E. Monroe" in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat regarding his marriage to "Miss Ella E. Owens," that took place in Clinton, Illinois. Why the notice was of interest in St. Louis is not in evidence, it may be a clue that Monroe lived in St. Louis, perhaps at the St. James Hotel, which was pretty common in the 19th century.

|

Wm. E. Monroe marries

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

November 29, 1884

|

(Click image to enlarge)

Was Monroe an associate or friend of Soapy's? Perhaps someone Soapy wanted to meet up with? Could Monroe been an early gang member, or was he a victim of Soapy's swindles? Perhaps a potential target to swindle? - Line 2: "St. James Hotel:"

- Line 3: "St. Louis Mo.:" The city and state where the St. James Hotel is located. Of note is the fact that St. Louis is not mentioned elsewhere in the STAR notebook, so was Soapy's visit a spur of the moment trip? Was "W. O. Monroe" a target of Soapy's before, or perhaps after, his arrival?

|

St. James Hotel

St. Louis, Missouri

1880s |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 23 - Original copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 23 - Enhanced copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy

|

(Click image to enlarge)

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 23 - Negative copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

Soapy Smith STAR Notebook

Page 23 - Deciphered copy

1884

Courtesy of Geri Murphy |

(Click image to enlarge)

- Line 1: "Dec 31st 1883:" According to Star notebook page #6, Soapy, in his own handwriting, was operating in Tombstone, Arizona between December 17, 1883 and December 22, 1883. Four days later, on December 26, 1883, Soapy paid $4 for a vendor’s license in Phoenix, Arizona. According to a blog post (December 26, 2009) and the San Francisco Chronicle (December 30, 1883) Soapy arrived in San Francisco on December 30, 1883, from Point Arena, California (Daily Alta, California, December 30, 1883). The newspaper clipping below indicates that Soapy arrived by steamer.

|

"Jeff Smith, Texas"

San Francisco Chronicle

December 30, 1883 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Note that "Jeff" lists that he is from "Texas." It was common for Soapy and other bunko men to list places they had not been in a while, if at all. This kept him from being extradited back to towns where he might be wanted by the courts. Soapy rarely wrote "Georgia," as his home state, probably to keep family there ignorant of his criminal escapades. Certainly, Soapy might have forged "friendships" with, perhaps paying, the hotel managers and employees to allow his returns without informing the police. Perhaps even forging his name to the hotel registration book, for "proof" against any criminal charges ("look, I signed the hotel registration on the date I am accused of a crime outside of San Francisco. I am innocent").

The following day he wrote “Dec 31st 1883" on this notebook page.- Line 2: "License [$]7.50:" He purchased a vendors license in San Francisco, California, for $7.50. This was a common practice for Soapy, as it often protected him from being arrested.

- Line 3: "Lawyer Jan 2, 1884.” It was a rare occurrence, but sometimes Soapy did get arrested.

|

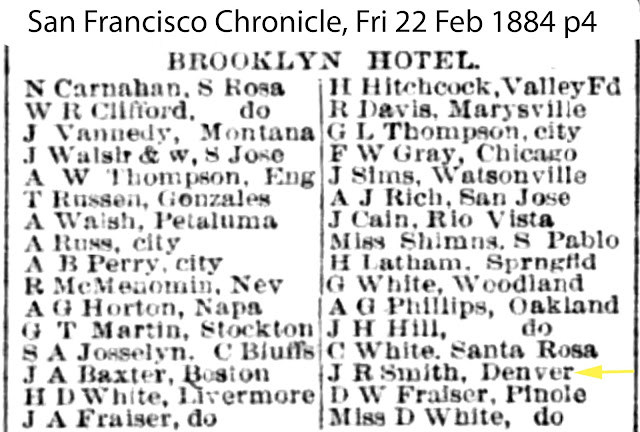

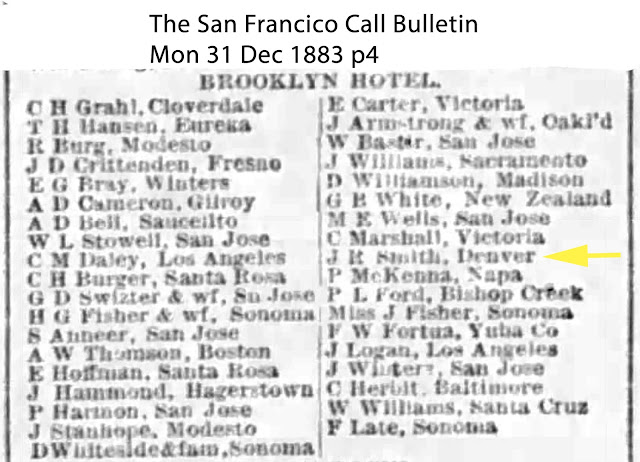

"J R Smith, Denver"

San Francisco Call-Bulletin

December 31, 1883. |

(Click image to enlarge)

On December 31st "J R Smith" [Jefferson Randolph Smith II] is listed as registering at the Brooklyn Hotel. On New Year’s Day, January 1, 1884, Two days after arriving in San Francisco, Soapy is arrested for operating the “soap racket.”

Rarely was Soapy ever around long enough to get arrested, let alone, stay around long enough for the police and newspapers to learn his name, but for some reason he remained in San Francisco, bucking the system. He may have been seeking to make San Francisco a base of operations, building his first criminal empire, just as he had tried to do in Tombstone, Arizona, but he was not successful in either endeavor. Likely, there was already a bunko gang in power, who drove young Jeff from their turf. In less than a year he would successfully build his own empire in Denver, Colorado.

The San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, January 3, 1884 describes the events of his arrest.

.jpg) |

"Jeff Smith's Soap Racket"

Daily Evening Bulletin

January 3, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Jeff Smith’s “Soap Racket.”

A sharp young man, Jeff Smith by name, who has been working the “soap racket,” as it is called, to large crowds on the street corners in the business part of the city for several weeks, was obligated to suspend operations at the corner of California and Front streets this morning at the request of Detectives Ross, Whittaker and Colby. They compelled him to fold up his camp-stool, strap his valise and go with them to the city prison, where he was charged on the register with conducting a lottery game. He appeared a trifle disturbed at the interruption, for it is not probable that he will gull simple countrymen for some time to come. For some time past complaints have come to the police regarding certain swindling soap vendors, whose plan of operations have been … about the same as Moses’ plaint to the Vicar of Wakefield after his return from the fair. Smith it seems has been in the habit of setting up his stock by opening his valise containing small packages of soap wherever he thought he could attract a crowd. His soap sold for fifty cents a package or three for one dollar, but the attraction was that he rolled greenbacks, one dollar and five dollars, in the packages before the eyes of the crowd, but by skillful manipulation the purchasers never obtained a lucky package. About a month ago another vendor was arrested, but allowed to go on his promising to leave the city. Smith was arrested at the ocean beach on New Year’s day, but as he also promised to leave, was allowed to go.

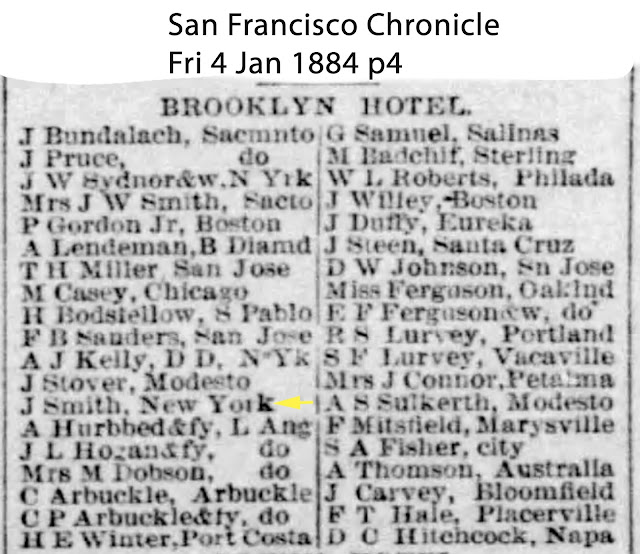

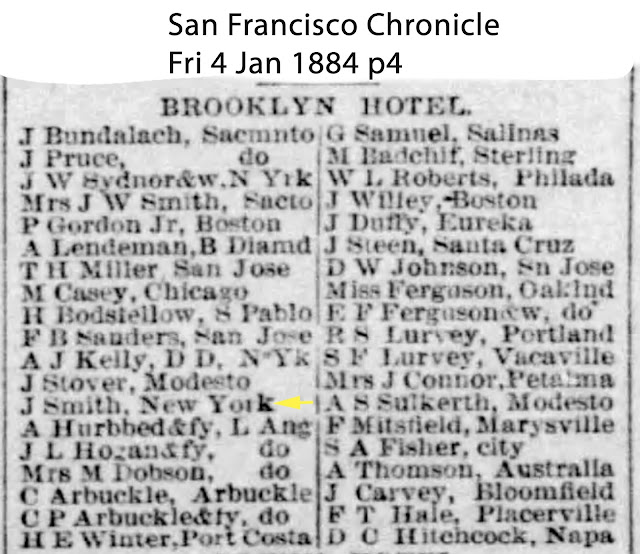

"He appeared a trifle disturbed at the interruption, ..." Very interesting that Soapy felt "disturbed at the interruption" by the police. It would not be the last time that Soapy Smith defiantly defended his occupation. The following day, the San Francisco Chronicle lists "J. Smith, New York" having registered in the Brooklyn Hotel.

|

"J Smith, New York"

San Francisco Chronicle

January 4, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

On the day of his arrest (January 3), or perhaps the following day, January 4, 1884, Soapy may have returned to the Brooklyn Hotel. However, it is possible that the "J Smith, New York" could be someone other than Soapy.

The San Francisco Chronicle published their version of Soapy's operations and arrest.

|

"A Soap-Vending Swindle"

Jeff Smith Arrested

San Francisco Chronicle

January 4, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

A Soap-Vending Swindle.

Jeff Smith was arrested yesterday by Detectives Ross, Colby and Whittaker and charged with conducting a lottery game. Smith is a vendor of soap and has been making himself conspicuous of late by offering that article for sale on street corners at 50 cents a package or three packages for $1. But the great attraction was that he rolled one and five-dollar greenbacks in certain of the packages, before the eyes of all present, but by some skillful manipulation the lucky packages never fell to any of the purchasers. He was arrested on the beach, New Year's Day, but allowed to go upon promising to leave the city. It is the intention of the police authorities to suppress this system of swindling, if possible, as many people have of late been victimized.

On the same day, the San Francisco Examiner also published what they knew of Soapy's operations and arrest.

|

"Smith's Antiquated Swindle."

San Francisco Examiner

January 4, 1884

|

(Click image to enlarge)

Smith's Antiquated Swindle.

Jeff Smith, the greenback soap seller, was arrested yesterday morning by Detective Whittaker and officer Colby for conducting a lottery game at the junction of California and Market streets. The detective was forced to obtain the assistance of the other officer for the reason that "spotters" were on the outskirts of the crowd to warn the cheat of the approach of the police. Smith's soap, which is about the size of a postage stamp, is sold by him for 50 cents a package or three for $1, but the attraction is in the greenbacks rolled in the packages before the eyes of the crowd. Smith's dexterous manipulation of the packages resulted always in the purchaser receiving nothing but the soap, the "cappers" being the only successful players at the game. With this very antiquated swindle Smith gathered in the pocket-money of pleasure-seekers on the ocean beach New Year's Day. He was arrested then and allowed to go on a promise that he would leave San Francisco.

Note that the article mentions "cappers," men (shills) working for Soapy. That's evidence that Soapy was not working alone. Although bunko men like Soapy, rarely worked alone, Soapy seldom mentions his cappers and shills, which has been in question throughout this notebook and the history of Soapy's early days of operating as a nomad confidence man.

All three newspapers reported that Soapy was allowed "to go on a promise that he would leave San Francisco." later newspapers state that he was arrested and had to appear in court. It seems he was arrested twice, perhaps even three times? Was he allowed to leave the city, but decided to stay and continue working? Likely that payoffs were involved.

According to some newspapers, Soapy had been in San Francisco for several weeks, operating his "soap racket." This time frame is confirmed by his signing the register at the American Exchange Hotel on October 31, 1883 (Daily Alta California and the San Francisco Chronicle)

|

San Francisco Chronical

"Jeff Smith"

Hotel Arrivals

October 31, 1883 |

(Click image to enlarge)

"Jeff Smith, do:" Do is an abbreviation for "ditto," a term meaning 'a duplicate,' in this case, of "Guernvl," short for Guerneville (California). As Guerneville is 75 miles north of San Francisco it is possible that he was there?

In the latter 19th century, the location around Guerneville was heavily timbered, and Guerneville was at the center of it with a big saw mill. It was linked by rail to ferry service in San Francisco Bay as it had become popular with people from the Bay Area wanting a getaway to the woods. Also there needed to be a way to move the lumber from the saw mill. So could it be that the four gentlemen who listed "Guerneville" before and after Soapy signed his name, be bunko-sharps that Soapy was working with? "Cappers" are mentioned working with Soapy in the San Francisco Examiner, January 4, 1884. The newspaper listing of "hotel arrivals" is not in alphabetical order, but rather in the order from which the men signed the hotel register. So what are the odds that five men who signed the register, one-after-another, were all coming from the same city? Were they together" Perhaps part of the wide-ranging soap-selling tour of California after leaving the northwest? The target clientele could have been visitors to the area as well as dirty loggers who could be made interested in soap with possible prize money. Or did Soapy simply copy what others above him registered under?

On January 8, 1884, after possibly being held in jail for as much as seven days, Soapy had his appointment in court, and his attorney was successful in getting the charges dismissed, but Soapy is "immediately rearrested on an amended complaint."

|

DISMISSED AND REARRESTED

Soapy's day in court

San Francisco Chronicle

January 8, 1884

|

(Click image to enlarge)

The charge of conducting a lottery game against Jeff Smith, the soap vendor, was dismissed, but he was immediately rearrested on an amended complaint.

So, what was the "amended complaint?" A new grievance case, or the same case that was just dismissed? Three days later the

San Francisco Bulletin, January 11, 1884 published the following.

|

Jeff Smith, the "soap racket" man

San Francisco Bulletin

January 11, 1884

|

(Click image to enlarge)

―Jeff Smith, the "soap racket" man arrested recently under the lottery ordinance, was discharged from custody yesterday by Police Judge Lawler, who held that the offense charged did not come under the provisions of the ordinance.

Probable is that San Francisco in 1884 lacked knowledge regarding the city ordinance pertaining to bunko-men and their games of no chance. At minimum, it was enough for Soapy's attorney to fight and win the case. Very possibly Soapy escaped prosecution through bribery, which may be a clue via line #4 below.

- Line 4: "Cash $20.00:" Is this the fee for the attorney, or possibly the payoff amount to Police Judge Lawler?

Though $20 does not seem like much money for a payoff, we must remember that in 1884 that $20 is the equivalent of $710.86 in 2025.

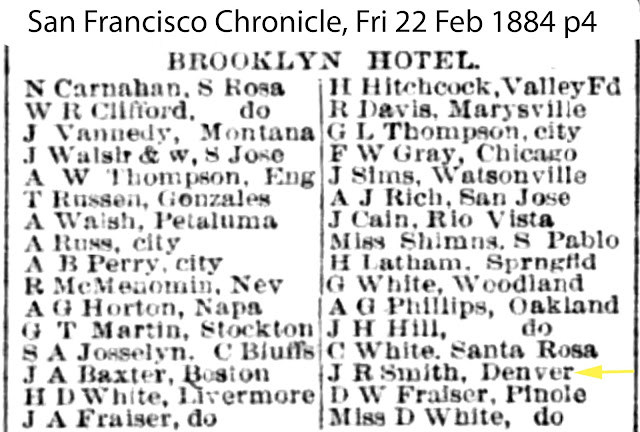

For the next 46 days Soapy is on the move, restlessly commuting to and from San Francisco, California, in a mysterious record of break-neck travel beginning on January 13, 1884, perhaps meant to keep ahead of being arrested by the San Francisco police, and/or working towns on the outskirts around San Francisco and down in southern California. Soapy travels to and from San Francisco with mere days in between, registering in hotels, namely the Brooklyn Hotel in San Francisco, sometimes leaving and re-registering in the same hotel, seemingly several times a day. The Brooklyn Hotel is no stranger to Soapy. He is recorded as registering there as early as October 30, 1882 and November 23, 1882. Following, is the rather lengthy record of his known travels during this period.

In pondering about what Soapy did in San Francisco for so long got me to looking more closely at where he resided in San Francisco. That turned up "J Smith" and "J R Smith" many times over among names listed under the heading "Hotel Arrivals." When names appear, they are, as the heading indicates, the names of "new arrivals." So, subsequent lists under this heading presumably do not include the names of those still residing at the hotel. Soapy's name appears many times among the new arrivals at the Brooklyn Hotel, meaning he is newly arrived again and again. Sometimes names of places he is from are of places around the Bay Area (Redwood, Hayward, Sonoma), but sometimes from other places (New York, Melbourne, Denver, Fort Worth). To be concluded is that Soapy left San Francisco and returned there numerous times. Shown are the many times he returned, not how many days he stayed in San Francisco or when he left. Newspaper searches of California at large for this period does not record him elsewhere except on passenger lists and, finally, checking into the St. Charles Hotel in Los Angles on 28 Feb 1884.

|

Brooklyn Hotel

Circa 1875

San Francisco, California |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

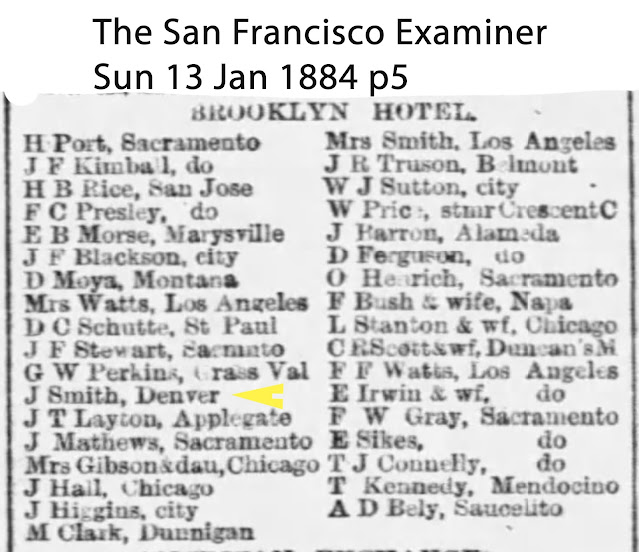

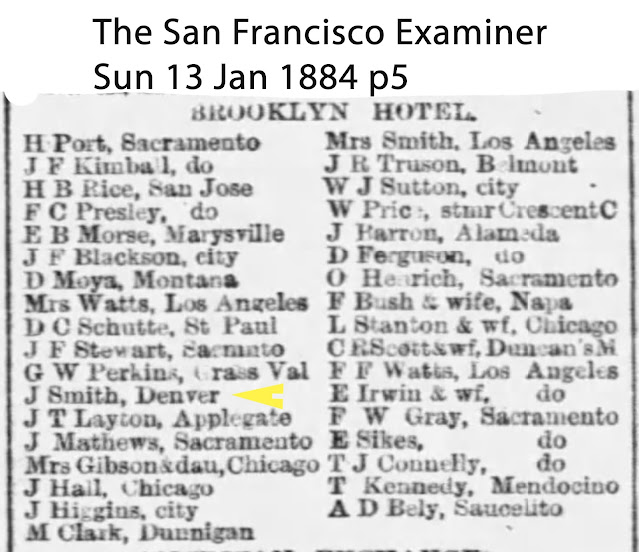

"J Smith, Denver

San Francisco Examiner

January 13, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

January 13, 1884 Soapy registers in the Brooklyn Hotel. As newspapers during this period published the "at the hotels" at different times, sometimes on the day customers sign the registers, and sometimes days later. Most of the time the registers were signed on the previous day of the newspaper publication. So, above the publication is dated January 13, we can guess that Soapy actually signed the hotel register on January 11-12.

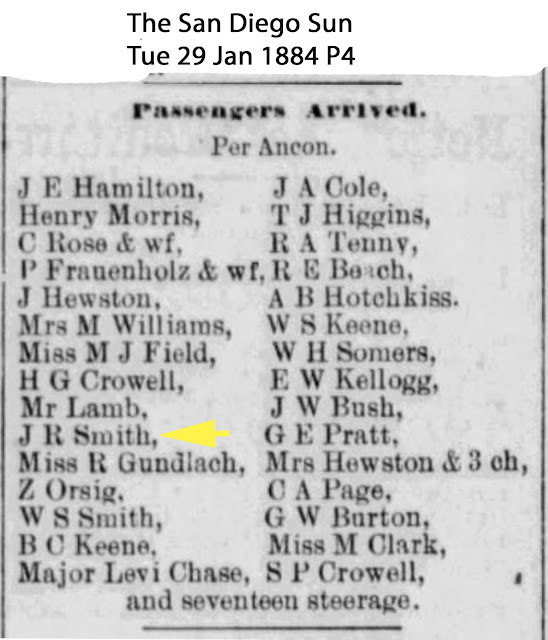

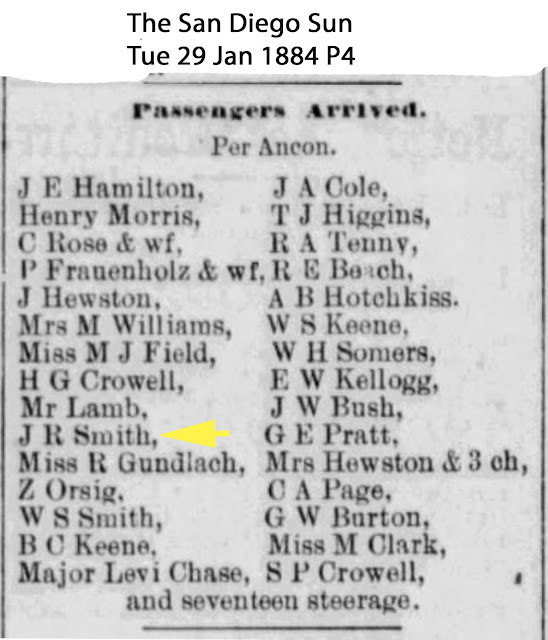

|

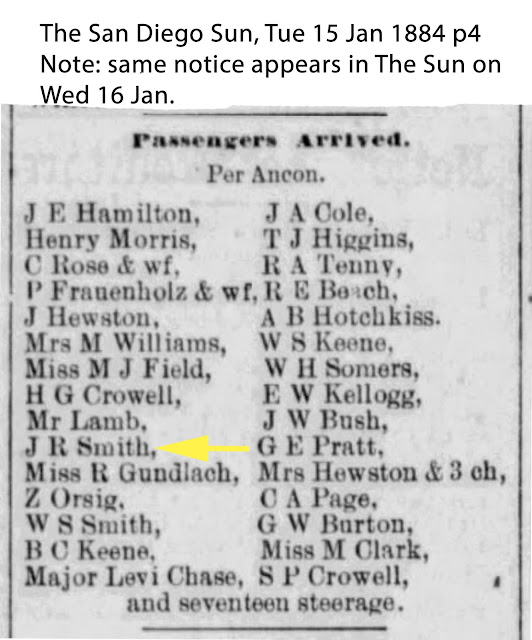

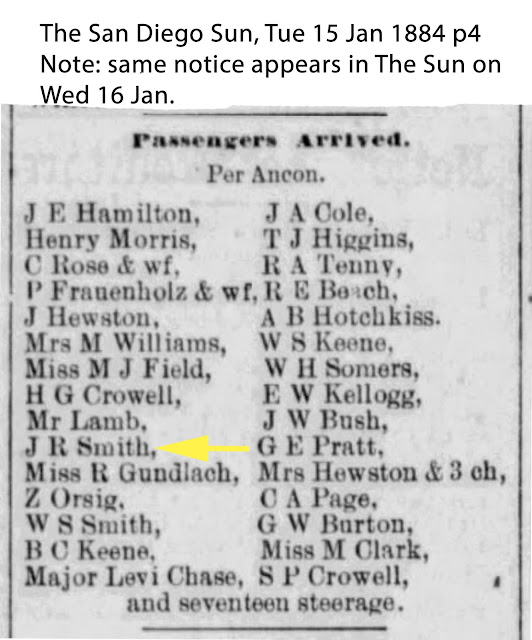

"J R Smith"

Arrives at San Diego "Per [steamer] Ancon"

San Diego Sun

January 15, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Two or three days later, the San Diego Sun, January 15, 1884, lists "J R Smith" arriving in San Diego, California, on board the steamer Ancon. Two days later the newspaper shows Soapy returning to San Francisco on board the Orizaba.

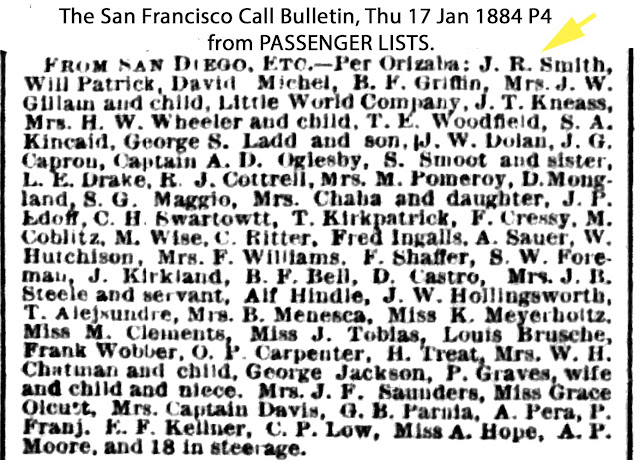

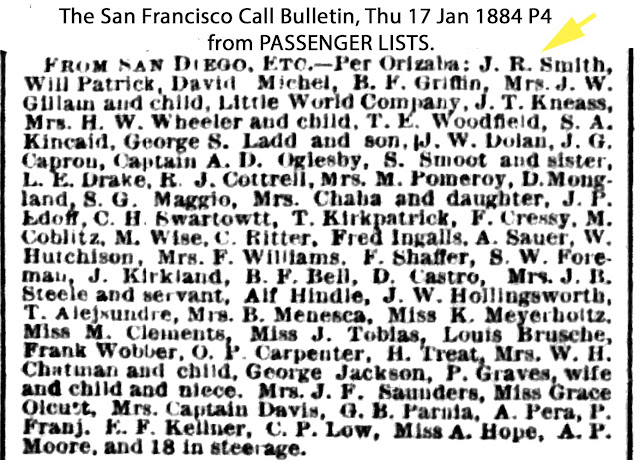

|

"J R Smith"

Arrives in San Francisco

On board the steamer Orizaba

San Francisco Call-Bulletin

January 17, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Soapy returns to San Francisco on the steamer Orizaba, arriving from San Diego on January 16, 1884.

|

| Steamer Orizaba |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

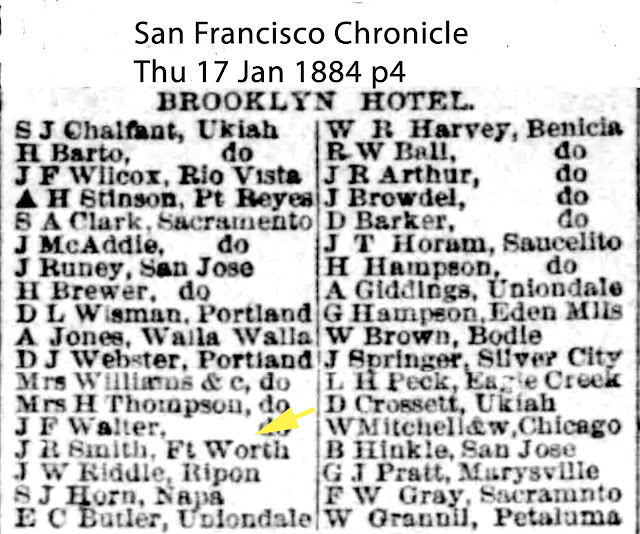

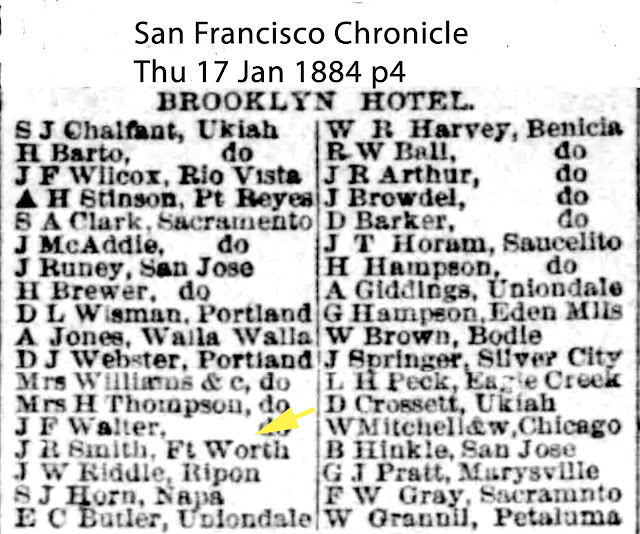

"J R Smith, Ft Worth"

Registers at the Brooklyn Hotel

San Francisco Chronicle

January 17, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

On the day of his return to San Francisco, January 16, 1884, Soapy registers in the Brooklyn Hotel, under his name, "J R Smith, Ft. Worth" [Texas] as reported in the Chronicle on January 17th.

|

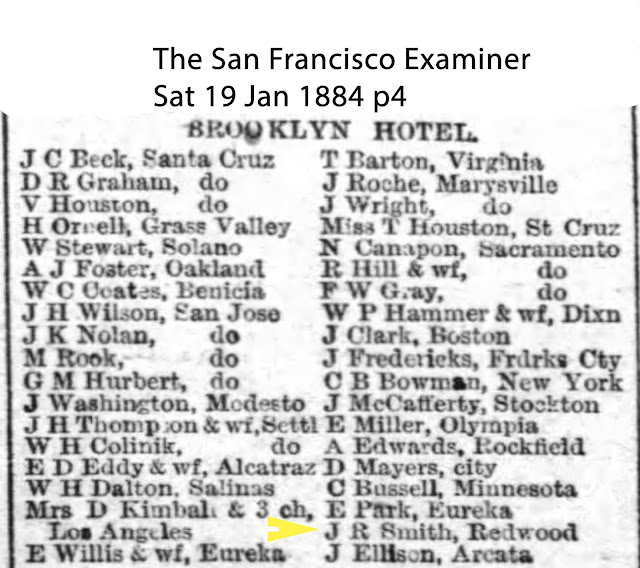

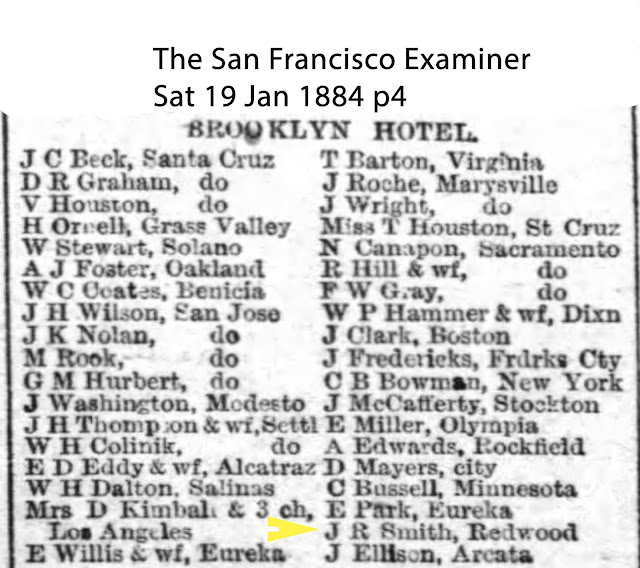

"J R Smith, Redwood" [California]

San Francisco Examiner

January 19, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

About two days later, on January 19, 1884 "J R Smith, Redwood" [California] registers at the Brooklyn Hotel. Why and when did he leave the hotel? Could Soapy have been operating in other towns outside of San Francisco? Was he perhaps warned that the police knew of his return? Is this another J R Smith?

|

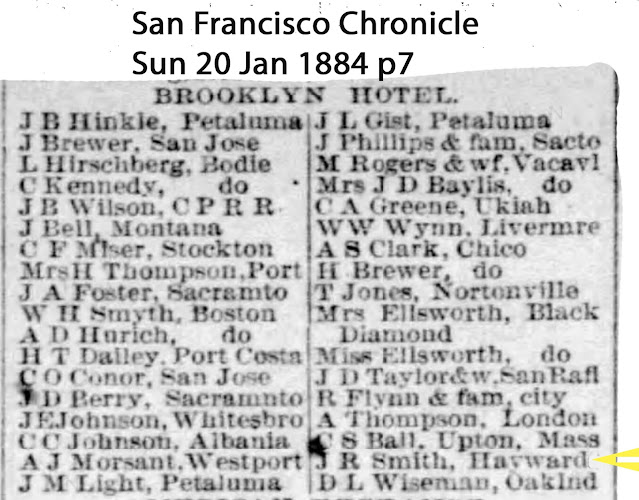

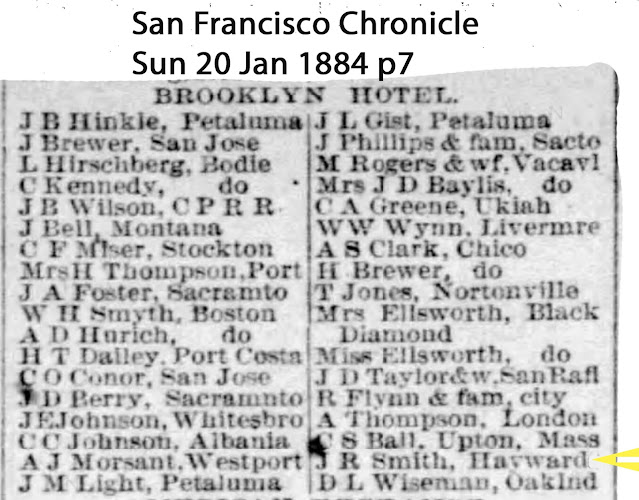

San Francisco Chronicle

January 20, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

The following day, January 20, 1884, Soapy registers in the Brooklyn Hotel, under "J R Smith, Hayward [California]. Normally, I would believe that the Chronicle published the same hotel registrations a day later than the Examiner, but why would Soapy's hometown change from Redwood to Haywood? Also, the names of the other registered guests are different. So why is Soapy registering and checking out of the hotel on a daily basis? Again, could Soapy have been operating in other towns just outside of San Francisco? Could this be another J R Smith?

|

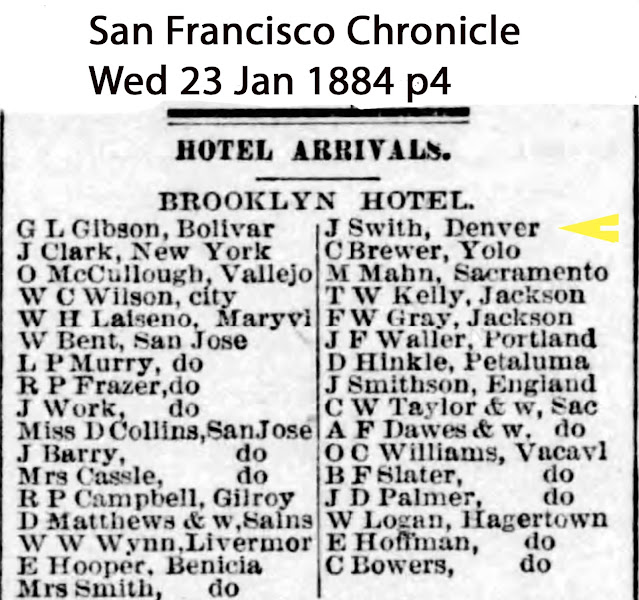

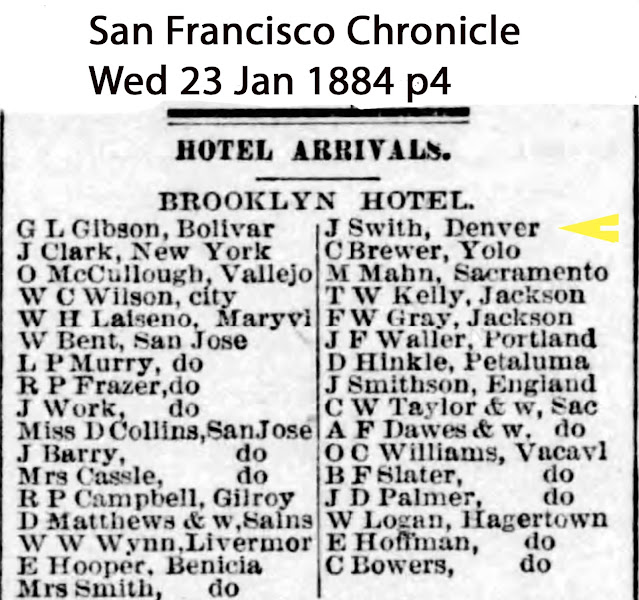

"J Swith, Denver"

San Francisco Chronicle

January 23, 1884 |

About three days later, January 23, 1884, J. Smith of Denver registers at the Brooklyn Hotel. Note the misspelling of "Smith," with a "w" in place of the "m." Was this an accidental error by the newspaper, or did if Soapy, did he intentionally/unintentionally misspell his name?

|

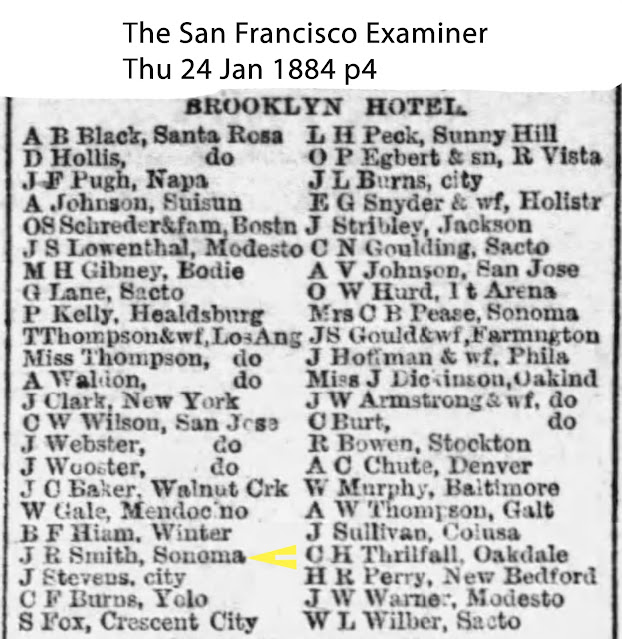

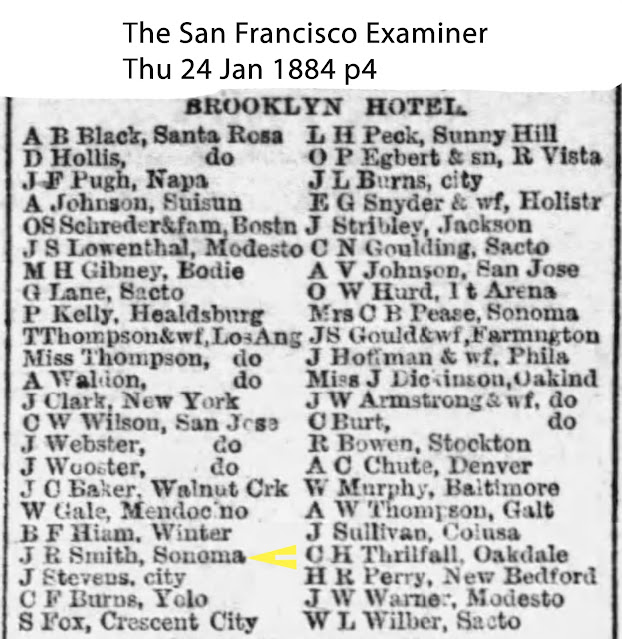

"J R Smith, Sonoma" [California]

San Francisco Examiner

January 24, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

The following day, January 24, 1884, the Examiner published "J R Smith, Sonoma" [California] registering at the Brooklyn Hotel. Normally, I would assume that the Chronicle and the Examiner published the same hotel registrations, with the Examiner publishing one day later, but why would Soapy's hometown change from Denver to Sonoma? Also, the names of the other registered guests are different in each newspaper. Why is Soapy registering and checking out of the hotel seemingly on a daily basis? Again, could Soapy have been operating in other towns just outside of San Francisco? Are there other J. R. Smith's.

|

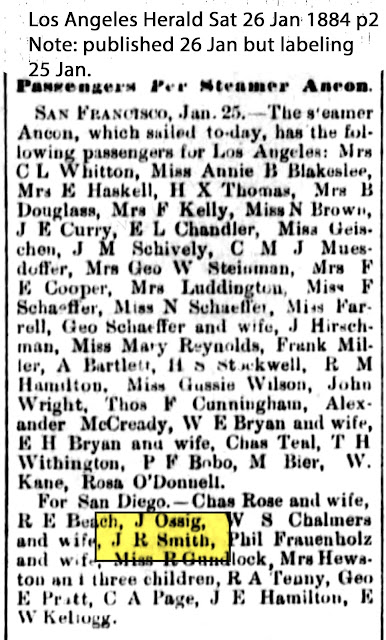

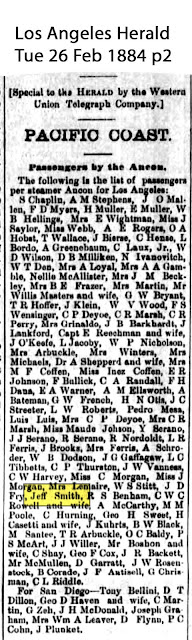

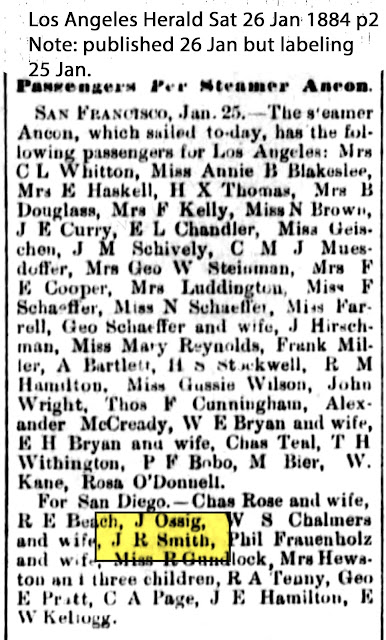

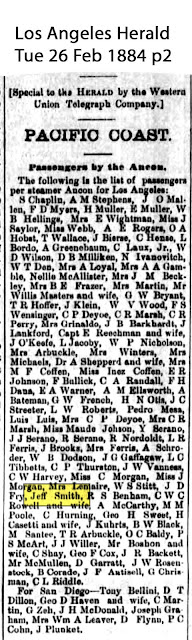

"J R Smith"

Los Angeles Herald

January 26, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

The following day, January 25, 1884, J. R. Smith leaves San Francisco heading to San Diego, California on the steamer Ancon.

|

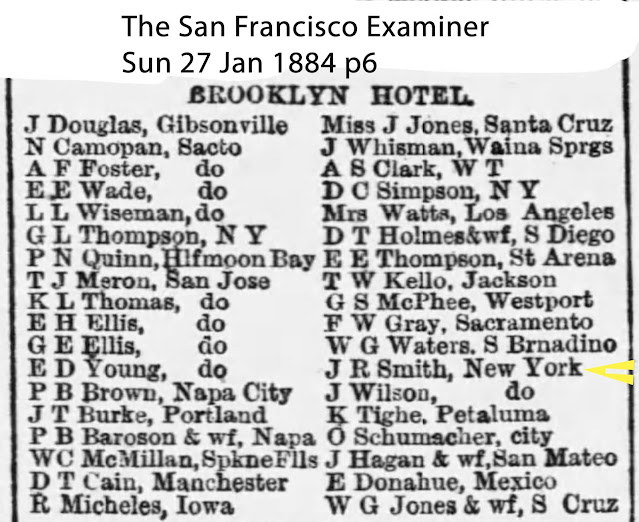

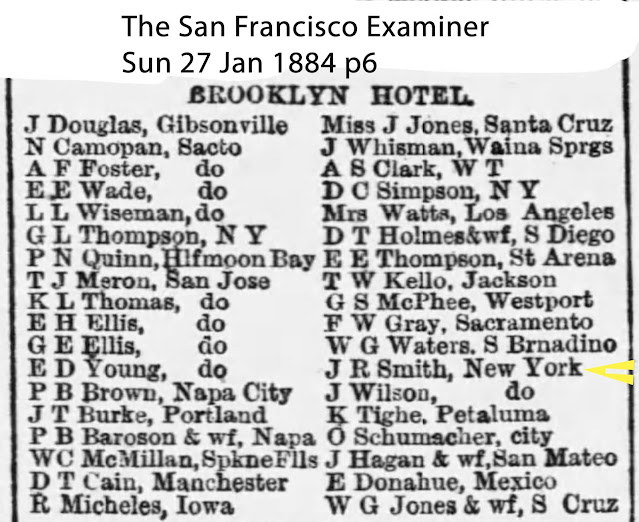

"J R Smith, New York"

San Francisco Examiner

January 27, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

About two days later, January 27, 1884, "J R Smith" is in/back in San Francisco registering at the Brooklyn Hotel, listing New York as his hometown. I am guessing that he signed the register on the 25th or 26th. Ship time tables show that it is not possible to sail from San Francisco to San Diego in a mere two days, let alone sailing back to San Francisco in that same two days. So there's the mystery. Did Soapy even board the

Ancon? If he did, where did he go? Was boarding the ship a ruse? Did he buy a ticket to throw off the police and/or any enemies? Are there more J. R. Smith's in the city at the same time?

|

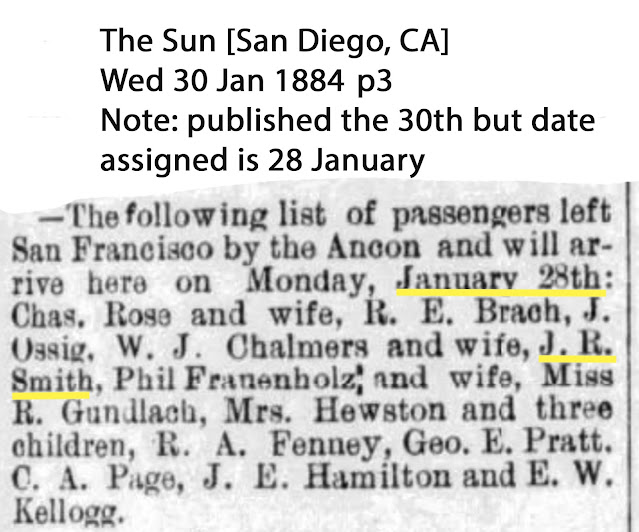

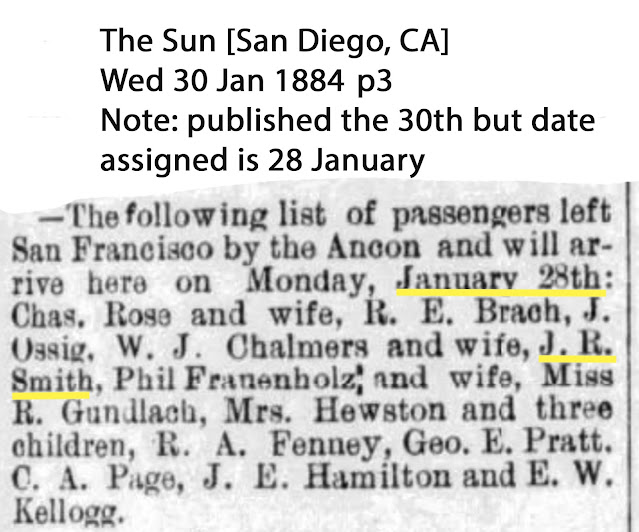

"J R Smith"

The Sun

January 30, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

A few days later, January 28, 1884, Soapy, or another Smith, arrives in San Diego aboard the Ancon. The timing indicates something is not as it seems.

|

"J R Smith"

San Diego Sun

January 29, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

The

San Diego Sun records "J R Smith's" arrival in San Diego, California, on January 28, 1884.

|

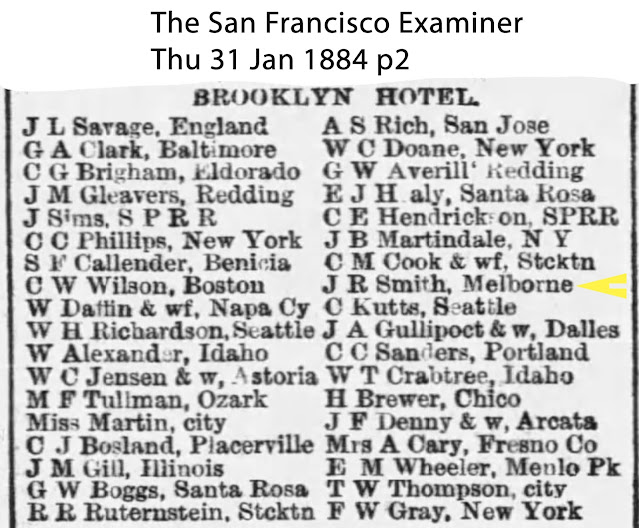

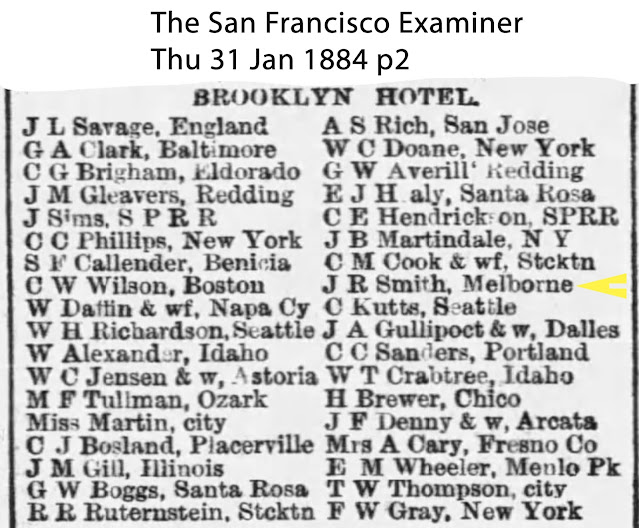

"J R Smith, Melborne" [sic]

San Francisco Examiner

January 31, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

January 31, 1884, several days later J R Smith is back in San Francisco at the Brooklyn Hotel, registering his home as "Melborne" (sic). At first I though he might mean Melbourne, Florida, but that city was not incorporated until 1888. It's possible that Soapy meant Melbourne, Australia. Again, note that most of Soapy's hotel registrations list a different hometown each publication. This was to throw off any investigation. It's certainly throwing off the research on Soapy's time in San Francisco.

|

"J R Smith, Tombstone"

San Francisco Examiner

February 6, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

About a week later, Soapy again registers at the Brooklyn Hotel, this time listing Tombstone, Arizona as his hometown. It is not known yet, where he went and why. I will guess that he has been operating swindle games around and outside of San Francisco.

|

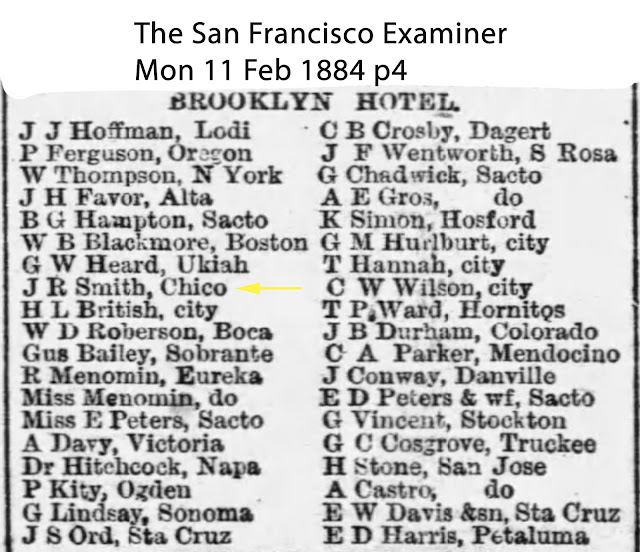

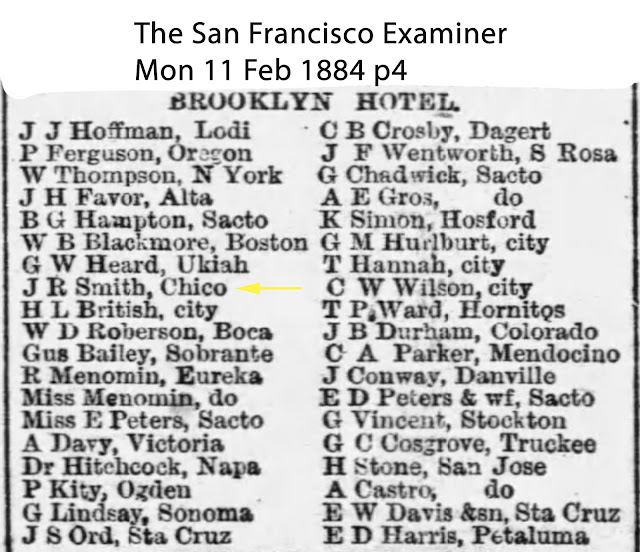

"J R Smith, Chico"

San Francisco Examiner

February 11, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

About four or fives days later, The

San Francisco Examiner lists J. R. Smith (Soapy?) registered at the Brooklyn Hotel, listing his hometown as Chico, California. It is not known at this time where he went, or why.

|

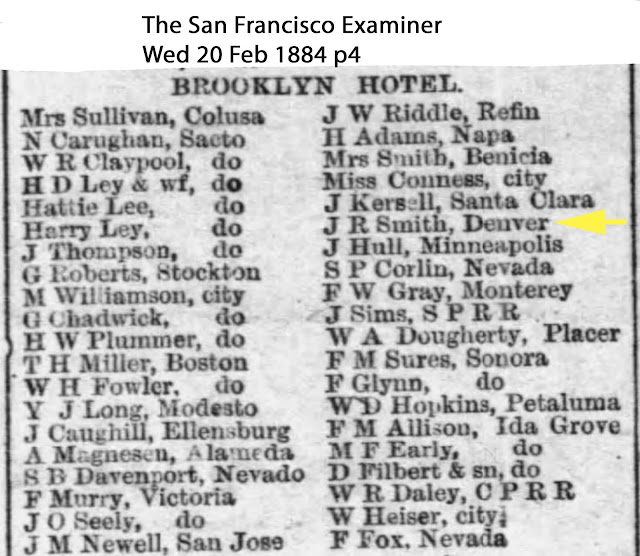

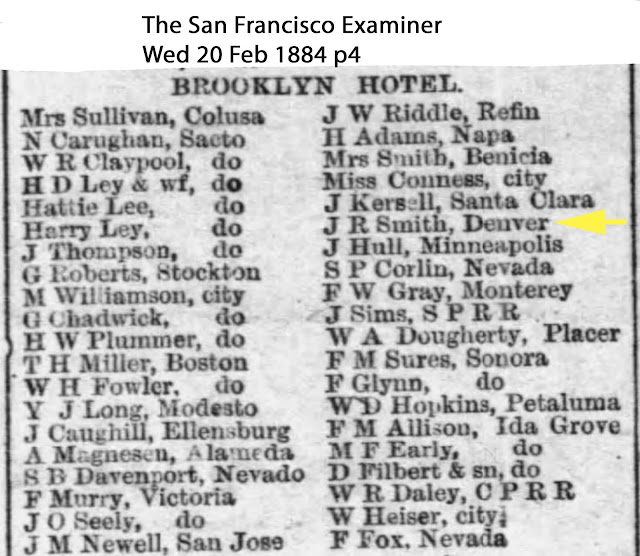

"J R Smith, Denver"

San Francisco Examiner

February 20, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

About nine days later, February 20, 1884, Soapy (likely) registers at the Brooklyn Hotel, listing Denver as his hometown. In 1884 Soapy was just beginning to rise in Denver as the kingpin of a future criminal empire and political fixer. In 1884 there were two bunko bosses in Denver, they being "Big Ed" Chase, who would later partner with Soapy, and Charles L. "Doc" Baggs. On the same day, Soapy is arrested for a stud poker swindle. He

saves the newspaper clipping.

|

"Stud-Horse" Poker

San Francisco Call-Bulletin

February 21, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

"Stud-Horse" Poker.

In Police Court No. 1 yesterday a charge of gambling against a number of young men, who were arrested for playing "stud-horse" poker, was dismissed on motion of the Prosecuting Attorney, who stated that the game was one of skill and not of chance.

An article comment on stud-poker by California magician James Lewis, in the

Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1985, indicates that the game was illegal in the state.

I think it’s fair to assume that the game prohibited by the California Legislature in 1884 under penalty of fine and imprisonment was at that time called “stud horse poker,” known today simply as stud poker.

As for politics and poker being old bedfellows, it’s interesting to note that the most lavish of San Francisco’s poker palaces during the 1870s was owned by one Charles Felton, who later became prominent in California politics. Perhaps Mr. Felton had some say in the banning of “stud horse poker” in our fair state.

|

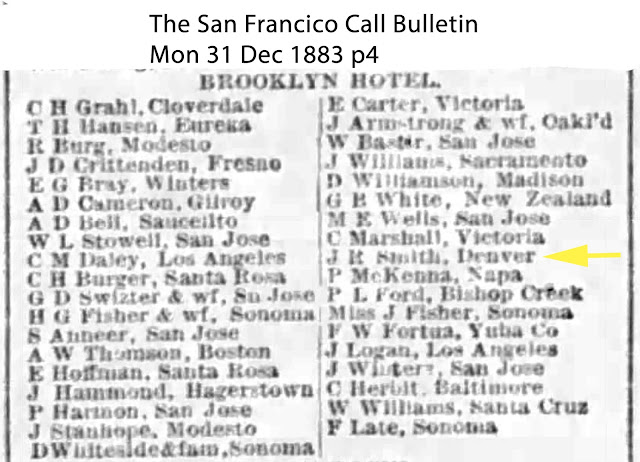

"J R Smith, Denver"

San Francisco Chronicle

February 22, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Two days later the newspaper shows "J R Smith, Denver" (likely Soapy) registering at the Brooklyn Hotel, which may be a repeat of the same register listings in two different newspapers, as a couple of the names are repeated, but most are not.

During this period, Soapy Smith arrived in San Francisco on December 30, 1883 and left, February 25, 1884. After spending 57 days, seemingly trying to set up a new empire, Soapy left San Francisco for Los Angeles and then to Denver where he successfully created his first criminal empire.

|

"Jeff Smith"

Steamer Ancon for Los Angeles

Los Angeles Herald

February 26, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

According to Soapy's notes in the Star notebook (page 24) Soapy boards the steamer

Ancon heading to Los Angeles, California on February 25, 1884.

|

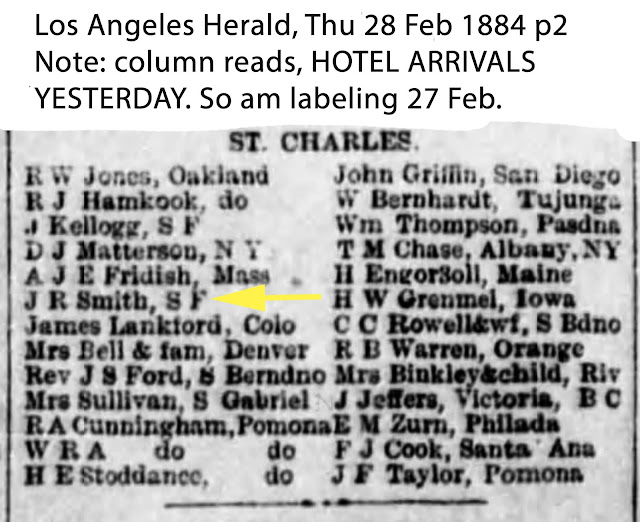

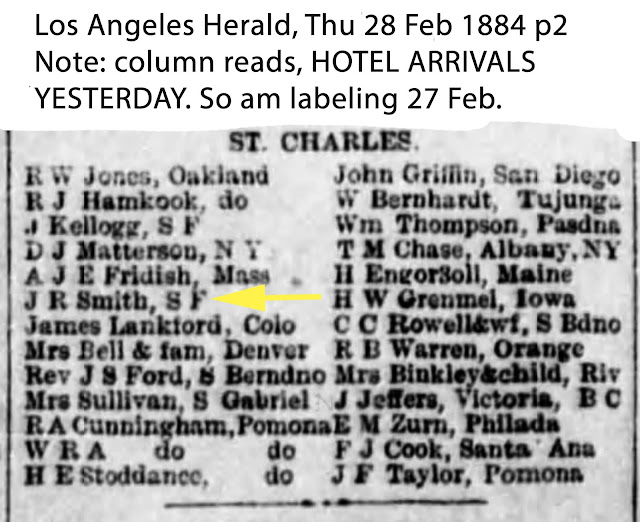

"J R Smith, S F" [San Francisco]

Los Angeles Herald

February 28, 1884 |

(Click image to enlarge)

On February 27, 1884, Soapy arrives in Los Angeles, California, registering at the St. Charles Hotel, listing his hometown as San Francisco.

|

St. Charles Hotel

Los Angeles, California |

(Click image to enlarge)

ADDING NEW INFORMATION

So what was Soapy doing? Was he alluding the law? Perhaps he was taking trips, operating outside of the city? One thought is that perhaps there are two "J R Smith's," but why would the "other" Smith list different hometowns in the hotel register like Soapy does? Are the different cities listed as his hometown hints as to where he went to and/or came from?

Check names of fellow travelers such as G. Bush, who may be gang members.

ADDENDUM

Under the San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1883, newspaper clipping above, Soapy "Jeff Smith" has registered at the American Exchange Hotel. There is an ongoing possibility that four men listed in the "Hotel Arrivals" might be bunko operators traveling and working with Soapy. I asked, "So could it be that

the four gentlemen who listed 'Guerneville' before and after Soapy signed his name, be bunko-sharps that Soapy was working with? "Cappers" are mentioned working with Soapy in the San Francisco Examiner, January 4, 1884. Were they part of the wide-ranging soap-selling tour of California after leaving the northwest?"

Art Petersen and I researched our newspaper archives under the four names listed with Soapy, as arriving from "do" (ditto) indicating "Guerneville." They are R. G. Longley, W. McNeal, James Murdoch, and George Huntley. The searches covered years 1880-1895, all across the Western states and territories.

The names, which very well may be alias,' of the four men are

- R. G. Longley

- W. McNeal

- James Murdock

- George Huntley

R. G. Longley:

The first name, listed as arriving from "Guernvl" (Guerneville, California).

|

R. G. Langley/Longley

San Francisco Chronicle

October 14, 1889 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Two newspapers showed registrations at the American Exchange on Oct 31, the Call Bulletin and the Examiner. The Examiner has a longer list, and it shows another name from Guerneville, R. G. Langley. This name appears separate from the other four names. A later clipping from 1889 names Langley as a "prominent lumberman" from Guerneville. Note the use of "a" instead of an "o" (Langley/Longley). Was this just an error in spelling the surname, or did R. G. intentionally misspell it to aid in escaping any arrest? Maybe his name appearing separately among the names has significance because it strongly suggests that the other 4 from Guerneville were likely traveling together as they would seem to have registered together. This appearance doesn't prove they were together, but registering separate from the lumberman strengthens the suggestion.

|

R. Langley arrested

Virginian-Pilot

Norfolk, Virginia

March 23, 1893

|

(Click image to enlarge)

R. Langley, petit larceny; ninety days in jail.

Petit larceny (or petty larceny) is a legal term for the theft of property valued below a specific dollar amount set by state law. It is typically a misdemeanor offense, punishable by fines or a jail sentence, distinguishing it from grand larceny, which involves higher-value property and carries more severe felony penalties.

This "R. Langley" is a criminal thief, but, is this R. G. Langley? I could not find enough newspaper accounts to determine who this is, and whether it was just a coincidence that his name is listed with "Jeff Smith's" name in the hotel register.

W. McNeal:

|

J. W. McNeal arrested

Dallas Daily Herald

July 21, 1881 |

(Click image to enlarge)

J. W. McNeal, a notorious character and outlaw, was lodged in jail at Columbus Monday.

Is J. W. McNeal and W. McNeal the same individual?

|

W. McNeal at the Antlers Hotel

The Weekly Gazette

September 5, 1885

|

(Click image to enlarge)

In early September 1885 W. McNeal arrives in Colorado Springs and registers at the Antlers Hotel, but no other appearances occur until 1889. There was another W. McNeal, an acclaimed actor who had a national reputation. This actor McNeal seems highly unlikely that he worked as a shill, capper, or gang member for Soapy.

|

W. McNeal registers at the Antlers Hotel

Center of photo

1885

Colorado Springs, Colorado |

(Click image to enlarge)

|

McNeal arrested for swindling

North Dakota Pioneer

May 5, 1889 |

(Click image to enlarge)

R. W. McNeal is in court on a charge of swindling, with an accomplice, Cole Grant, in Hamilton county, Iowa. They were convicted of the charge. The question remains, is this the W. McNeal Soapy travelled with?

James Murdock:

In 1887 a James Murdoch is tried and convicted in Ohio of murder. He was sentenced to hang, but took his own life. Still could have been James Murdoch who arrived in San Francisco with Soapy Smith.

|

James Murdoch, murderer

The Blade, (Toledo, Ohio)

December 15, 1887 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Three years later, another James Murdock (Murdoch?), a gambler by trade and a member of the Nestlehouse gang, is arrested in Omaha, Nebraska on the charge of being a fugitive from justice in Davenport, Iowa. His crime there is unknown. I could not find anything on the Nestlehouse gang. It is not known if this James Murdock/Murdoch is the same man who may have been with Soapy in San Francisco.

|

James Murdoch ("Murdock")

gambler, fugitive from justice

Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, Nebraska)

February 16, 1890 |

(Click image to enlarge)

Eight months later, October 16, 1890, a James Murdoch is arrested in Omaha, Nebraska as a "suspicious character."

|

"As a highway robber"

James Murdoch ["Murdock"]

Omaha World-Herald

Omaha, Nebraska

October 17, 1890 |

(Click image to enlarge)

AS A HIGHWAY ROBBER.

The police detectives last night arrested James Murdoch as a suspicious character, but his friends soon bailed him out. The arrest was made on a letter received from Chief of Police Kessler of Davenport, Iowa, who in reply to a query, stated that Murdoch was under $500 bail there for committing highway robbery, and that he is a mean fellow capable of committing any crime.

No more was found on James Murdoch.

George Huntley:

|

George Huntley

Knights Templar

Passenger list

San Francisco Chronicle

August 11, 1883 |

(Click image to enlarge)

When I read of George Huntley being a Knights Templar, my thoughts ran to soap gang member John L. Bowers and his glad-handing of victims with his collection of fraternal and organizational pins and knowledge of organization handshakes, as a means of luring in victims in Denver.

The George Huntley who showed up in SF twice, beyond the George Huntley with the Guerneville group, was reported coming to SF on 28 July 1883 and 11 August 1883. He is twice reported as a member of a Knights Templar group from Pennsylvania. Research in the Pennsylvania newspapers about the Kendron Commandery No 18, seems legit, with swords, regalia, and a history, but that doesn't mean it was rogue free. Probably, though, the Guerneville Huntley and the Pennsylvania Huntley are two G. Huntley's.

|

Major George Huntley

Passenger Lists

Omaha, Nebraska

San Francisco Chronicle

July 28, 1883 |

(Click image to enlarge)

The names of the four men and the newspaper articles will be saved for future reference as possible short-lived members of the early soap gang. There is just not enough evidence or information either way to make a definitive decision regarding these individuals.

PAGE 23 OF THE STAR NOTEBOOK WILL CONTINUE ON PAGE 24.

Notebook pages

Notebook pages

April 24, 2017

Part #1

Part #2

Part #3

Part #4

Part #5

Part #6

Part #7

Part #8

Part #9

Part #10

Part #11

Part #12

Part #13

Part #14

Part #15

Part #16

"He made fortune after fortune and spent it all in riotous living and in good deeds, for it must be ever said of "Soapy" that no hungry man ever asked aid of him and was refused."

——San Francisco Examiner, February 25, 1898

.jpg)