HE “BUNCO STEERER.”

His “Modus Operandi” as Described by a Recent Victim.

His “Modus Operandi” as Described by a Recent Victim.

The following publication from the Abilene Reflector, May 14, 1885, is about a typical account from the victim's view of an encounter with a bunco gang. The interesting difference in this particular article is that it is told in great detail, from start to finish. Though this bunco gang was based in New York, its "modus operandi" is nearly identical to the theatrical performances used by con man "Soapy" Smith and the soap gang in Denver, Colorado, in 1885-1895.

THE “BUNCO STEERER.”

His “Modus Operandi” as Described by a Recent Victim.

His “Modus Operandi” as Described by a Recent Victim.

Remember, then, what, when a boy, I’ve

Heard my grandma tell:

“Be warned in time by others’ harm, and you

shall do full well!”

Don’t link yourself with vulgar folks, who’ve

Got no fixed abode,

“Tell lies, use naughty words, and say “they

Wish they may be blowed.”

—Ingoldsby Legends.[1]Since the time of the benevolent old gentleman of Margate who was so shamefully robbed by “the little vulgar boy,” other benevolent old gentlemen—and young ones, too—have been made the victims of the smooth-tongued gentry.

It is wonderful how slow we are to learn by the sad experience of others. Although numberless cases of misplaced confidence have been duly exposed in the public press, yet several travelers from the rural districts, who pay occasional visits on business or pleasure to the large cities, always prove themselves sure game for the various types of cheats who eke out a perilous livelihood by trading upon their credulity.

The world never will hear the complete details of all the tricks played on the unwary. Many who have come to grief reason philosophically that they have bought their sad experience at the price of the amount out of which they have been cheated, and so will not by recourse to the aid of the authorities, and its consequent publicity, allow themselves to be the butt or laughing stock of their friends.

Foremost among the many cheats of all varieties who are always sure to infest thickly populated localities, are the “bunco” men. Their methods are very simple, and are unfortunately too often attended with success. A “bunco steerer” must, however, bring some brains into his nefarious calling, and it is sometimes wonderful to see what keen perception and persuasive faculties, which, if honestly applied, would win distinction for their possessor, are brought into play by the “bunco sharpers.”

It takes a little ring of confederates to carry on this game successfully. There is first the “spotter,” who scouts out, as it were, the game, and then quickly apprises the “beaters,” who, if they succeed in hooking their man, pilot him into the hands of the lottery man and his confederates, who “play the greeny” for all he is worth, and then instantly vanish to meet again at some pre-arranged trysting-place, where the “swag” is honorably (?) “divied up.”

The reader is familiar with the oft-recited details of the “bunco” man’s method: how the victim is accosted by a stranger in mistake and his name and address are secured, and then, armed with this valuable information, some young friend whom he has forgotten addresses him by his name and with an insinuating manner, of which the “bunco steerer” is complete master, wiles him into a saloon or a lottery shop, where the coup de grace is given, and, a sadder, wiser and poorer man laments over his misadventure.

A too-confiding old gentleman, who does not give his real name, has furnished us with that portion of his diary which relates to a “bunco” trick. As it is eminently graphic and quite comprehensive, we think it unnecessary to indulge in further comment, so give it to our readers in his own exact words:

SANDUSKY, O., April —. 1885. —To the Editor of — Sir: I send you herewith, according to promise, the leaves from my diary bearing upon the little trouble I got into in New York. As I do not wish my charitable neighbors in this locality should have the pleasure of commiserating with me, you will please withhold my proper name and for all purposes of identity and in this narrative call me yours truly. —JOHN SMITH.

THE DIARY.

I am at home, safe and sound in Sandusky, thank God for that! And save that I am a little poorer in pocket and somewhat crestfallen in spirit, I am none the worse for my adventure. I had a little business to transact in New York, which could have been, perhaps, as well done by letter, but then a bachelor of my time of life often like to run away from the dull routine of home surroundings to experience for a while the bustle and unrest of a great city.

I never travel without money. Some people tell me it is dangerous to carry about with me as much as I do on these occasions. Perhaps it is, but having had a sad experience in my youth of a journey I undertook without being burdened with the circulating medium, I have arrived at the conclusion that a fair allowance of money in one’s pocket is an essential ingredient to one’s enjoyment when out in the pursuit of health or happiness.I did not encumber myself with much luggage, but merely filled my pocket-book with moderate sized bills, took a little hand valise with a necessary change of clothing, and full of good spirits and philanthropy duly installed myself at the Astor House.

I like lounging about the Astor House rotunda and steps. One can pick one’s teeth, meet an occasional acquaintance, and delight one’s gaze with the motley collection of human beings to be met there upon any day in the year.

It was old Dr. Johnson, I think, who said, when asked for material for thought and description: ”Let us take a walk down Fleet Street.” Now, if the old doctor were alive in these days, and on a lecturing tour in America, and if asked what public promenade he would suggest to engender food for mental reflection he would, in my opinion, certainly reply, “Let us take a walk on Broadway.”

I don’t exactly know whether I was thinking of the learned Doctor or not, or whether I was allowing my mind to wander fancy free, as I strolled up Broadway to make a call upon a friend. For convenience, I had placed a lot of papers and other matters in my hand valise, and, having plenty of time at my disposal, I lounged along, gaping from one side to the other and reflecting meditatively on the babel of sounds and the immense throng of people who surged and rushed in all directions.

(Click image to enlarge)

I think I had just passed Canal Street, when I was accosted by a rather genteel kind of man, who timidly stretched his hand out as if to greet me, and then, gazing at me with deep intent, said: “How d’ye do, Senator?”

“You mistake, my good fellow,” said I, elevating one hand and warding off his advances. “I have not the honor of being a member of the Legislature, but am only a plain citizen and a mere visitor in this city.”

“Well, well, well,” repeated the shabby-genteel party, “’tis really extraordinary. I could take my oath you were Senator Spoonbill; the same height, side-whiskers, long hair and dignified, gentlemanly appearance. Excuse me, sir, but you are not really joking?”

“I assure you, on my honor,” said I, impressively, as I withdrew out the throng of passers-by, “that I was never more serious in my life. I am not Senator Spoonbill, but plain John Smith, of Sandusky, O.”

“Dear me!” ejaculated the rather genteel party, “I should never have thought so. Besides, one of the Senator’s eccentricities is always to carry in his hand a black traveling bag with many of his valuables inclosed in it, just such a one as you have in your hand at present.”

“My friend,” said I, “I know nothing of the Senator’s peculiarities, and furthermore I am not the man to carry my money or valuables in a hand bag, which might be snatched from me by the first desperado I should meet. No, sir; whatever money I carry about me is safely inclosed[sic] in my pocket-book, where the thief or designing rascal can not even see or lay a hand on it.”

“You do quite right, sir,” meekly replied my new acquaintance, and I hope you will excuse me for the mistake I made in stopping you.”

“Don’t mention it, my friend,” I replied, encouragingly. “The likeness, as you said, was so striking that you are not to blame, but before I leave you let me give you what we call down in Sandusaky ‘a pointer.’ Never carry your valuables in a hand-bag like your acquaintance, the Senator. Keep your money safely rolled up in your inside vest pocket, and then you can laugh at the thieves, ha! ha! ha!”

With a chuckle of satisfaction at my own humor and a bow of respectful recognition at parting, I continued my walk up Broadway.

|

| The second bunco man moves in and introduces himself. Abilene Reflector May 14, 1885 |

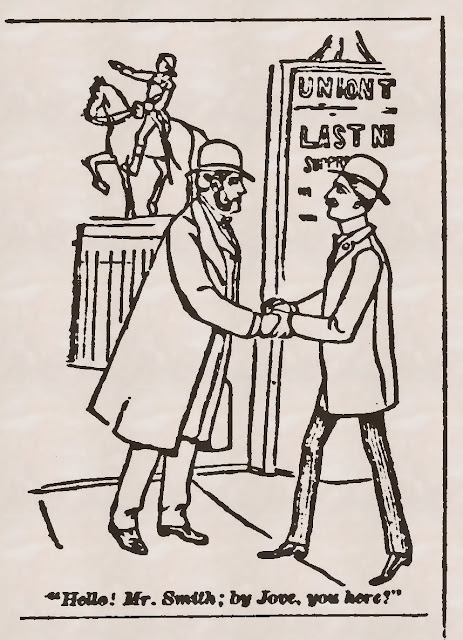

(Click image to enlarge)

I can’t exactly say how I ever cultivated the taste for looking into shop windows. I know that every window I passed during the next half hour was scanned by me with such attention that I almost seemed to myself to be indulging in the process of appraising the value of goods set out for show. As I was turning the corner of Fourteenth Street, entering into Union Square, a foreign-looking young man, somewhat dudeishly attired, recognized me, and rushing over, grasped me firmly by the hand saying: “Hello, Mr. Smith: by Jove, you here? What in the name of wonder brought you down from Sandusky?”I was a little nonplussed at this warm greeting from a stranger, but as he knew me I thought it wiser to await developments, and said, with some politeness:

“O, just ran down on a little business, and hope to be back home in a few days; but, you will excuse me, I cannot exactly place you, although you seem to know me very well.”

“Know you,” said my friend, with evident delight. “I should smile!” Why, Mr. Smith, I knew you when I was a mere child. How long have you been living in your present residence?”

“Well,” said I, “ever since my brother and myself dissolved partnership, and I retired from business.”

“And how is your brother now?” he inquired.

“How?” I said, in some surprise. “How the deuce can I tell? He was the first man incinerated in the new crematory. I guess what’s left of him is all right at home on the mantle-piece.”

“Poor fellow,” said my young friend, with some sadness in his tone, “it was so sad, his taking off.”

“Yes,“ said I, “You seem to have known him well. He was too fond, unfortunately, of taking rum at unseasonable hours, and that’s how he got so quickly incinerated. But might I ask your name?

“Come, now,” he replied, “look me straight in the face and give a guess. Mind, though, I have been out of Sandusky a long time, knocking about Europe, and I am on my way home now, not like the prodigal son, either, as I have been in luck of late, and only this morning drew a prize of a thousand dollars, which I am this moment on my way to get cashed. But that is another matter. Now, as to my identity, I wish to please you with a surprise. Do you know the manager of the First National Bank?"

“Do I! I should think so. He is my own banker, and as decent a fellow as ever I met. There’s not another man in the state of Ohio I have a greater regard for than Joe Hawley.”

“Did you ever know that Joe had a son who went away to Europe?”

“No; not as I’ve heard, young fellow. Joe is, like myself, an older bachelor, and all the boys he ever took an interest in were his nephews, Jim’s son’s. I guess one of them, Egbert, or Eggy, as they used to call him, did run away, but I always heard that he kinder got his blood up agin the Indians.”

“No, sir; you are on the correct trail, but we must leave the Indian war-path. I gave it out that I was going West, but, by Jove! I did better and went East, made money in England, and now I am on my way back with lots of money to see dear old Sandusky.”

“My dear boy,” said I. “I am delighted to meet you, and if you are not in a particular hurry to go home, guess you ought to wait for me. I am stopping, for the present, at the Astor House, and I am now on my way up to Sixteenth Street to meet an old Sandusky friend, D. Tobias Earwig.”

“Friends again, by Jove!” ejaculated my companion. “Do you know Dr. Earwig? The second man I called on after leaving the landing-pier a short time ago. I promised to call on him, too, this very afternoon. In fact, he placed it upon me as an obligation. But there’s no use your going there now if you wish to see him.”

“Why? May I ask.”

“Because he is at this moment giving a demonstration at the Clinical in Harlem Hospital. You must have patience like myself, until four o’clock, and we can call on him together.”

“Very good,” said I, resignedly; “I confess I am not in any great hurry, but I don’t relish the idea of walking about here carrying this confounded bag.”

“Then I’ll settle that. I don’t mind confessing to you that the joy of getting home again has made me do a little too much in going round to see the Elephant, you know; and I guess a glass of good wine—Yellow Label, old man—won’t at all be out of place in my stomach. In fact, Dr. Earwig, our mutual friend, ordered me to take it. Come on.”

|

| Enjoying the Yellow Label wine getting the victim drunk. Abilene Reflector May 14, 1885 |

(Click image to enlarge)

I don’t know now why I yielded to the invitation of this stranger; but there was something in his easy manner which must have prepossessed me in his favor, and as I had a couple of hours’ lounging to do I easily fell a victim to his toils.

My newly-found friend beckoned to a cabman, and before I could fully make up my mind, or even utter one word of expostulation, I was seated alongside him, and we were whisked up town at a rattling pace, until our conveyance stopped up with a sudden jerk at the door of a quiet-looking restaurant.

We had the Yellow Label, as my friend called it, and as it was really good wine I felt bound to order a second bottle, when an acquaintance of my friend joined us, and I was duly introduced to him. This friend would insist upon a third bottle of the Yellow Label, and all the time kept wishing my young Sandusky acquaintance joy over his good fortune in winning such a large prize in some lottery.

“Eggy,” said he, “I guess I’ll have another go at fortune. I have a few dollars which I can spare, and maybe I should have luck if you will only favor me with your—and your friend’s company.”“I don’t mind, old fellow,” was the reply. “Guess I want to get cash for my check, anyhow, but I won’t play any more, as I am going home to Sandusky as soon as possible.”

“Come on, then,” said the other, “here’s a cab at the door. I am in a hurry, and can’t stay more than half an hour, play or not play.”

I suppose it was the wine—Yellow Label—which rose in my head, but once more I found myself in a cab, and in a short time was ushered into a small apartment fitted up in office style, and my young Sandusky friend presented his check for payment.

The party in charge was very polite, and begged my Sandusky friend to wait a few moments until he procured a counter signature of some other official before handing out the cash. Meanwhile the other friend said he would try his luck, and depositing a ten-dollar bill on the desk drew a ticket out of a little revolving mahogany box. He won. I saw him paid out fifty dollars, and I then began to take an interest in the game. My Sandusky friend asked the man in charge if he would give him credit pending the arrival of his winnings from his check, and he was prepared to play he beckoned me aside and confidentially informed me that if I followed his example, and invested the same amount as he did, we could win as much as would pay all our expenses and leave us a nice balance in our hands on landing at Sandusky. Perhaps it was the effect of the Yellow Label stuff, or perhaps the fellow mesmerized me, but I unfortunately accepted his advice and drew out a ten-dollar bill, and we won fifty dollars each. One of the party then suggested that a bottle of wine should be opened to our good fortune, and after partaking of a glass, my Sandusky friend whispered me that he was going now for a thousand, which he would add to the thousand already owed him. Again I am forced to make the sad confession that I resigned myself blindly to his advice; but luck did not seem to cling to him, as he won and lost by turns until he commenced, as he called it, to plunge. Of course, I plunged too, and my big roll of bills, amounting to over $300, soon dwindled down to a very small sum, until to my surprise I found myself compelled to borrow from my friend. His finances were drained out as well as my own, so he whispered me to take a chair and wait for him for a few minutes until he should return with the cash requisite for us to take out our revenge.

(Click image to enlarge)

So I sat down and saw my young Sandusky friend politely bowing to me as he took his departure. I think I pulled nervously at my whiskers, and it began to dawn upon me that all was not as straight as it might be. I was thus engaged when a colored man rushed into the room and breathlessly informed me that he feared the police were at the front door, and I had better get out quickly by the back way, and take a cab to a place where my young Sandusky friend awaited me.

I yielded automatically, and after a half-hour’s drive in the up-town portion of the city, my cabby pulled up and handed me my small hand valise and said I was to wait at this spot until he went for Mr. Hawley, whom he had instructions to drive back and join me at this particular place.

I hadn’t even the presence of mind to take the number of that cab, my mind was in such a disturbed state; so I patiently waited for Hawley, who never turned up, although the shades of evening were approaching and the lamplighters were beginning to illuminate the district.

I suppose it must have been that Yellow Label business which so obfuscated my intellectual faculties. It was quite dark and I was beginning to attract the attention of the passers-by before it fully dawned upon me that I had been cruelly swindled. Seeing a colored lamp in the distance which told me I was in the vicinity of a police precinct, I instantly rushed toward it to state my grievances.

|

| Lodging a useless complaint at the police station. Abilene Reflector May 14, 1885 |

(Click image to enlarge)

I have a very great respect for the police force, but with all due respect for that highly intelligent body, the officer in charge smiled at me when I recounted my adventure, and, as he seemed to throw some doubts upon my sanity and jocularly remarked that, in his opinion, a good square sleep might take down the swelling in my head, I produced the only evidence of the swindle in my possession—a numbered ticket.

This seemed to have little effect, as this very incompetent officer only folded his arms on the desk, and smiled at me more and more.

“Go home, boss,” said he, “and when you next take a trip here from Sandusky, learn that it isn’t safe to stop and chin [to talk, chatter, gossip] in the streets with every one who says he knows you, and, above all things, keep a safe distance between yourself and the bunco steerer.”

—N.Y. Cor. Louisville Courier Journal.

NOTES:

[1]: The poem section comes from

Misadventures at Margate. A Legend of Jarvis's Jetty. Mr. Simpkinson loquitur. page 315

"The surest of all “sure things” is a game operated with three little shells. It is one of the oldest bunko games in existence. The newspapers have published columns about it, and the names if its victims are as the sands of the sea."

—Aspen Daily Chronicle, July 30, 1889