213 pages.

No index.

No Forward.

No Acknowledgements (understandable as he didn’t use any).

No photographs (except the cover).

No notes.

No Works Referenced.

No sources.

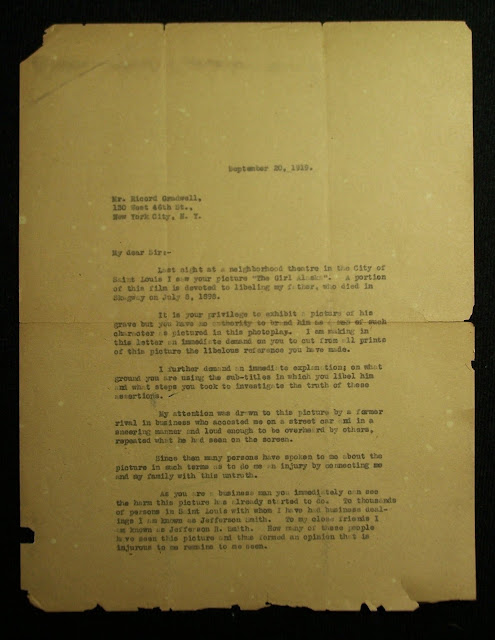

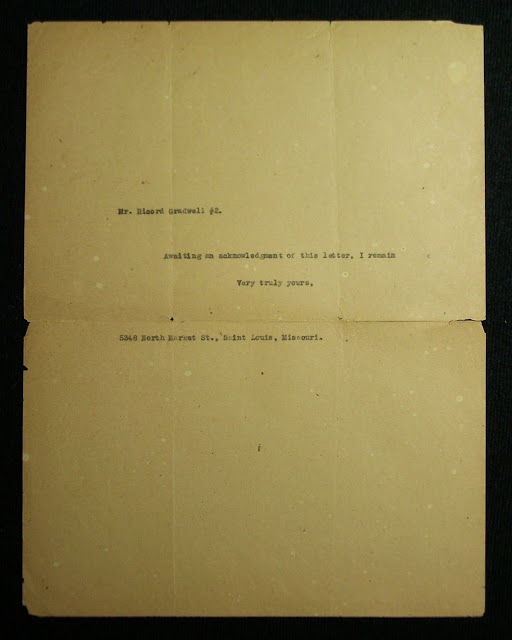

This is my review of the self-published book, Soapy Smith, published by Fred Spooner in April 2025. In short, this biography, if it can be defined as such, is a travesty to history. Of all the biographies on my great-grandfather, published since 1907, this one is without a doubt, the most poorly researched and written book to date. Besides information and artifacts, I collect books written about Soapy Smith, so I purchased this one by Mr. Spooner. I am not exaggerating when I say it was a tortuous and painful read.

Instead of actual information on Soapy Smith, Mr. Spooner chose to use his imagination, filler, and repeated points and information in nearly every single paragraph to stretch the books size to 213 pages, when the legitimate historical information could have been published in a considerably smaller book or article. The book contains no photographs (except on the cover), no listed notes or references, no index and no sources. Mr. Spooner promises “a nuanced, well-researched portrait,” but this promise is never realized, instead defending his “scholarly” (his words) work throughout the book that there is a “lack of detailed records.” The author skirts around having to do any research by instead, inventing events that never occurred. The author couldn’t even be bothered to find out the names of Soapy’s parents, his gang members, or anyone he associated with, except for “Frank Reid,” one of the vigilantes that shot Soapy during the shootout on Juneau wharf in Skagway, Alaska in 1898.

From this book I must conclude that the author did not investigate, read, or apparently know of the other well-known biographies on Soapy, including my own, Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. He either chose not to use, or did not investigate, the known research, letters, documents, etc., that exist, instead writing, “the limitations of primary sources are also evident in their absences. The lack of extensive personal diaries or detailed memoirs written by Smith himself limits our direct access to his thoughts and motivations.” The history of Soapy Smith is out there and relatively easy to find, but Mr. Spooner failed in performing the most rudimentary research. Instead, he guesses and invents his own version of Soapy Smith's history, all-the-while stating that his work is well-researched and scholarly.

In the preface, Mr. Spooner states, that “Through meticulous examination of primary sources – newspaper accounts, letters, and legal documents from the era – we strive to present a balanced account of Smith’s life, revealing the man behind the myth.” However, Mr. Spooner does not publish a single source, other than simply stating that he uses “evidence often found in later newspaper articles and accounts from those who knew him in later years.” In order to justify his non-existent research, he chooses to compare Soapy with other historic individuals, writing, “the absence of detailed information necessitates a comparative analysis,” giving him the freedom to invent history, which he calls a "nuanced, well-researched portrait.”

In the introduction, Mr. Spooner writes that “This biography seeks to move beyond the sensationalized tales and explore the multifaceted (he loves this word, using it many times throughout the book) nature of his existence offering a balanced historical analysis grounded in primary source materials,” but fails to deliver any “historical analysis grounded in primary source materials,” beating every bush to keep from exposing that he performed no actual research.

By page 5 I knew there was a major problem with Mr. Spooner’s “research” when under the chapter, “Early Life and Family Background,” he writes that Soapy was born in Iowa. Spooner uses no sources for this, defending his work, writing, “while definitive biographical details of his childhood remain scarce …” Which is absolutely untrue. He then wastes the readers time by expanding on Iowa’s history as the source for the history of early Smith family history, Soapy’s upbringing and education. I, and my family, have been researching Soapy's life and death for decades, and nowhere have I ever seen any publication or information stating that Soapy was born in Iowa! Smith family history, via genealogical records and sources, clearly shows that Soapy was born in Coweta, Georgia, and every published work I have in my collection states the same, so I have to wonder where Mr. Spooner found this tripe? I speculate that the author has previous information on Iowa and its history and thus chose that location as the birthplace to simplify his labor in this “well-researched portrait.” In short, he made it up, rendering this part of the book on Soapy's childhood and upbringing absolutely useless.

Mr. Spooner writes, “the westward migration of Jefferson Randolph 'Soapy' Smith … remains a somewhat hazy journal, shrouded in the same lack of meticulously documented record-keeping …” Again, the author gives excuses for his lack of research, while touting his book as being “grounded in primary source materials.” Furthermore, he writes, “Smith’s travel’s lack the same level of detailed personal accounts … absence of first-hand narratives.” Had Mr. Spooner performed the bare minimum amount of research he would have found that Soapy kept detailed records of his travels, via published letters and personal notebooks, which are seen online and in my book. After spending a little time on Soapy’s fictitious childhood, Mr. Spooner jumps twenty years to 1897-98 and Soapy’s time in Skagway, not mentioning, and probably not knowing that Soapy spent a decade as a crime boss in Denver, Colorado.

Regarding Soapy’s prize package soap sell racket, Mr. Spooner didn’t know that Soapy wrapped cash into the cakes of soap, instead, writing that Soapy wrapped “merchandise and inferior quality merchandise.”

Throughout the book Mr. Spooner uses the same excuse of, “there is no sources and information,” allowing him to make up the history. There are so little actual facts in this book that Mr. Spooner could have edited the book down to about ten pages, but opted to stretch the number of pages to 213 pages, via useless fictional filler and the act of repeating his points over and again for about 164 pages, the majority of the book, hence a tortuous and laborious read.

SKAGWAY

From this book I must conclude that the author did not investigate, read, or apparently know of the other well-known biographies on Soapy, including my own, Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. He either chose not to use, or did not investigate, the known research, letters, documents, etc., that exist, instead writing, “the limitations of primary sources are also evident in their absences. The lack of extensive personal diaries or detailed memoirs written by Smith himself limits our direct access to his thoughts and motivations.” The history of Soapy Smith is out there and relatively easy to find, but Mr. Spooner failed in performing the most rudimentary research. Instead, he guesses and invents his own version of Soapy Smith's history, all-the-while stating that his work is well-researched and scholarly.

In the preface, Mr. Spooner states, that “Through meticulous examination of primary sources – newspaper accounts, letters, and legal documents from the era – we strive to present a balanced account of Smith’s life, revealing the man behind the myth.” However, Mr. Spooner does not publish a single source, other than simply stating that he uses “evidence often found in later newspaper articles and accounts from those who knew him in later years.” In order to justify his non-existent research, he chooses to compare Soapy with other historic individuals, writing, “the absence of detailed information necessitates a comparative analysis,” giving him the freedom to invent history, which he calls a "nuanced, well-researched portrait.”

In the introduction, Mr. Spooner writes that “This biography seeks to move beyond the sensationalized tales and explore the multifaceted (he loves this word, using it many times throughout the book) nature of his existence offering a balanced historical analysis grounded in primary source materials,” but fails to deliver any “historical analysis grounded in primary source materials,” beating every bush to keep from exposing that he performed no actual research.

By page 5 I knew there was a major problem with Mr. Spooner’s “research” when under the chapter, “Early Life and Family Background,” he writes that Soapy was born in Iowa. Spooner uses no sources for this, defending his work, writing, “while definitive biographical details of his childhood remain scarce …” Which is absolutely untrue. He then wastes the readers time by expanding on Iowa’s history as the source for the history of early Smith family history, Soapy’s upbringing and education. I, and my family, have been researching Soapy's life and death for decades, and nowhere have I ever seen any publication or information stating that Soapy was born in Iowa! Smith family history, via genealogical records and sources, clearly shows that Soapy was born in Coweta, Georgia, and every published work I have in my collection states the same, so I have to wonder where Mr. Spooner found this tripe? I speculate that the author has previous information on Iowa and its history and thus chose that location as the birthplace to simplify his labor in this “well-researched portrait.” In short, he made it up, rendering this part of the book on Soapy's childhood and upbringing absolutely useless.

Mr. Spooner writes, “the westward migration of Jefferson Randolph 'Soapy' Smith … remains a somewhat hazy journal, shrouded in the same lack of meticulously documented record-keeping …” Again, the author gives excuses for his lack of research, while touting his book as being “grounded in primary source materials.” Furthermore, he writes, “Smith’s travel’s lack the same level of detailed personal accounts … absence of first-hand narratives.” Had Mr. Spooner performed the bare minimum amount of research he would have found that Soapy kept detailed records of his travels, via published letters and personal notebooks, which are seen online and in my book. After spending a little time on Soapy’s fictitious childhood, Mr. Spooner jumps twenty years to 1897-98 and Soapy’s time in Skagway, not mentioning, and probably not knowing that Soapy spent a decade as a crime boss in Denver, Colorado.

Regarding Soapy’s prize package soap sell racket, Mr. Spooner didn’t know that Soapy wrapped cash into the cakes of soap, instead, writing that Soapy wrapped “merchandise and inferior quality merchandise.”

Throughout the book Mr. Spooner uses the same excuse of, “there is no sources and information,” allowing him to make up the history. There are so little actual facts in this book that Mr. Spooner could have edited the book down to about ten pages, but opted to stretch the number of pages to 213 pages, via useless fictional filler and the act of repeating his points over and again for about 164 pages, the majority of the book, hence a tortuous and laborious read.

SKAGWAY

Mr. Spooner incorrectly writes that the steamship Portland brought Soapy to Skagway, but this is inaccurate. I believe he learned that in 1897 the steamship Portland arrived in Seattle, Washington, carrying prospectors and a ton of gold from Alaska, marking the beginning of the Klondike gold rush, and used that to deduce how Soapy arrived in Skagway. He writes that Soapy arrived in Skagway alone, but a little simple research would have shown Mr. Spooner that Soapy arrived with two other gang members, and that they profited almost $30,000 in 19-days work. Not a single source is noted, though he promised said sources. Amazingly, Mr. Spooner makes no mention of Soapy’s saloon, Jeff Smith’s Parlor.

The author invents a fictional shootout that he says occurred earlier in the day on July 8, 1898, the same day as the shootout in which Soapy was killed by Jesse Murphy and Frank Reid. He writes that this fictional shootout occurs on the corner of Broadway and Third Avenue, where Soapy had planned and held a "peaceful political rally" in which a minor scuffle escalated into a “full-blown gunfight that left several people injured and the streets awash in blood.” There are no mentions or sources, that that this fight ever took place, other than in Mr. Spooner's book. In fact, this is the first time I have ever heard of this event.

In the section on the shootout on Juneau wharf, Mr. Spooner states that Soapy died, “in Skagway’s streets,” which is completely false, as Soapy died on Juneau wharf. This fact is well-known, and just one more piece of evidence that the author did little to no research. Spooner also invents that numerous people, from "four to eight" were shot and killed or wounded, other than Soapy and Reid, all without any evidence or a single source.

SMITH’S PLACE IN HISTORY AND POPULAR CULTURE

Mr. Spooner writes, “He never became the subject the subject of a major biographical epic …” Besides my own book, there are numerous other biographies on Soapy. There are also several films, including Clark Gable’s Honky Tonk, centered on Soapy’s life, not to mention several well-done history documentaries.

REPEAT … AND REPEAT, OVER AND AGAIN.

The last 164 pages of the book are exhaustingly hard to read as the author chose to repeat the same points, over and over. It became nauseatingly difficult to read, and found myself skipping down pages looking for something, anything, new that Mr. Spooner had to say, but found nothing worth writing about. The author used filler and unrelated topics to stretch out the book size, including such topics as the social fabric of the indigenous populations, the introduction of diseases in society and other health problems, the environment, pollution, water contamination, etc., all having little to nothing to do with Soapy's history, because Mr. Spooner had so little information on Soapy to begin with.

In the author’s section titled, Suggested Readings and Additional Resources, he writes “This section presents a curated selection of resources, categorized for ease of navigation, to facilitate further exploration,” and then doesn’t include a single resource or example, giving the reason that “a definitive biography remains elusive,” obviously, not putting forth any effort to find, let alone read, any of the other biographies on Soapy.

In the chapter titled, Famous Con Artists and Their Methods, Mr. Spooner does not discuss other confidence men or their methods, instead choosing to discuss Charles “Black Bart” Boles, a stagecoach robber, not a con artist.

ABOUT FRED SPOONER

Mr. Spooner has published at least 56 books, all with the same cover, minus the use of a different photograph. I will assume that all of them lack much effort or research. I cannot find any other information or contact for this author.

CONCLUSION

In short, Mr. Spooner did little to no research, making up much of the history, rendering this book absolutely useless. If you wish to learn about Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith, I suggest not wasting your time and money on this book. As a Soapy Smith historian and collector I will keep this book in my collection, but if I was the average reader who happened to purchase and read this book, I would likely just toss this one in the nearest trash container.

"Soapy Smith - cleaning up the West - one pocket at a time"

—unknown