|

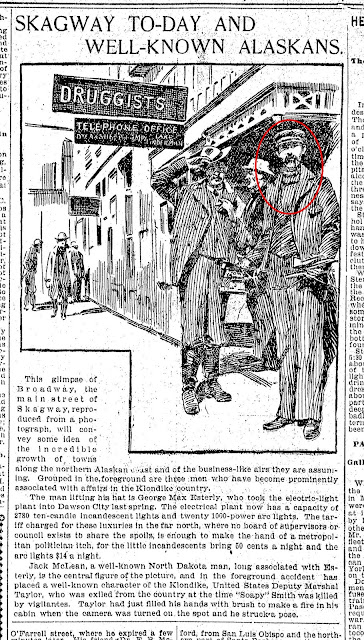

| Sylvester Slade Taylor Four months after Soapy's death San Francisco Chronicle November 3, 1898 |

(Click image to enlarge)

EPUTY U.S. MARSHAL SYLVESTER SLADE TAYLOR

(04/03/1867 – 05/12/1958)

The Latest On A Forgotten Lawman.

Deputy U.S. Marshal Sylvester Slade Taylor, known as "Vess" to his family, has a black mark upon his record as a lawman which appears to be one of the reasons he remains largely unknown. In Skagway, Alaska, 1898, he was under the pay of bad man Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith. After Soapy's death, via vigilantes, Deputy U.S. Marshal Taylor was "arrested" by the vigilantes along with members of the soap gang, charged with negligence of duty for his lack of performance after the robbery of miner John Douglas Stewart, and held until his boss, U.S. Marshal James McCain Shoup, arrived to relieve him of his duty. Historically, this is what Taylor is most famous for.

Other than his involvement with

Soapy Smith in Skagway, not much was known of Sylvester S. Taylor previous to 2010. In that year I had the pleasure of corresponding with

a descendant of Taylor (second cousin twice removed) a family

historian connected with the Ancestry.com profile for the Taylor family. This descendant wished to remain anonymous for privacy reasons

and I still respect her wishes to this day. At the time, the Taylor family was not

certain that their Sylvester Taylor was the same Deputy U.S. Marshal Taylor of Skagway, Alaska, fame. Even today the Ancestry profile mentions neither the lawman's profession nor his connection to Soapy Smith, however, there are solid links between the two that prove the two Taylors are one and the same.

In every empire Soapy constructed, one of the first hurdles to jump was bounding the courts and the law under his control. Large graft payments were a common necessity in order for Soapy and his men to operate in newly arrived camps and towns. In Skagway, Alaska, 1898, one of the hurdles was 31-year old Deputy U.S. Marshal Sylvester Slade Taylor, who replaced Deputy U.S. Marshal James Rowan after he was killed on January 31, 1898. There are no details of how or when Taylor was lured into the criminal side of the law and placed on Soapy’s payroll as it was kept secret until early June 1898 when Mattie Silks publicly accused Taylor of being involved with the murder and robbery of Ella Wilson as well as being instrumental in a plan to murder of Silks. All of this was according to Silks herself and is questionable. Details of her accusations and story are equally interesting and can be found in my book, Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel.

|

| Sylvester Slade Taylor Taylor and Maddox family reunion Palo Alto, Texas, August 6, 1922 From Taylor and Bevers Pioneer Families of Palo Pinto County, Texas by Bobbie Ross, 1996 |

Taylor’s final fall occurred after three of the soap gang swindled some funds and then outright robbed miner John Stewart’s gold in Skagway, Alaska, on July 8, 1898, which directly led to Soapy's death at the shootout on the Juneau Company Wharf. With the

collapse of soap gang rule in Skagway, the vigilantes rounded up the gang and accused Taylor of

being directly involved with Soapy, of silencing the news of the robbery, and of failing to arrest the culprits in the case. Vigilantes went to the home of Taylor to

arrest him, only to find him sitting in a chair holding a baby

(probably Stephan Alaska Taylor, born two months prior). Taylor was

ordered to stay inside his home or risk death. Later he was accused of

offering the return $600 of Stewart’s gold to Alaska’s Governor Brady if

allowed to leave Skagway a free man. This request was denied and Taylor

was charged with “willful neglect of duty.” [1][2]

U.S. Marshal Shoup arrived on Thursday, July 14, and within hours

fired Taylor from his position and appointed vigilante J. M. Tanner in his place. The Daily Alaskan reported “ex-Deputy Marshal

Taylor” was charged with "attempted extortion from a stampeder," but as the

complainant left Skaguay for the interior, that charge was set aside, leaving

only the charge of “willful neglect of duty, laid by Mr. Stewart.” Taylor was

brought before the Committee of Safety to answer to the charges against him on July 15, 1898.

“He waived examination” and was ordered held pending posting of $5,000 bond

until his trial at Sitka, Alaska. Deputy U.S. Marshal Tanner took Taylor into

custody.[3] Marshal Shoup later defended his hiring of Taylor, stating that when he appointed the

man, he came “with exceptionally strong recommendations, having served in a

similar capacity in Idaho …, where his reputation as an officer was

unassailable.”[4] From Taylor's hearing in Skagway, it was discovered that from 1891 to 1896, Taylor had been constable and

deputy sheriff in Nanpa, Idaho, and during a portion of that time, he was a

deputy US marshal, and from May 1896 to January 30, 1898, he had been city marshal

of Nanpa.[5]

Reverend R. M. Dickey wrote that he

associated with Taylor in Skagway, had dinner with him “and his friendly wife in

their snug home.” In the fictional account of his time in Skaguay,

Dickey characterized Taylor as “Strange and puzzling…,” “clever,” acting

“With great courage,” a man of feeling who “completely broke down” in

telling of a little girl who had died some ten years before.

And yet some people in Skaguay suspected that he was in fraternity with Soapy Smith and his league of cutthroats. We never believed that. And yet…. … Our conclusion was that he was a big-hearted man who fully determined to do right but who had in some way come under the power of Soapy and that he writhed under it. … There was something there, but whatever power Soapy had over him we never knew. It may be that he found himself powerless to enforce the law strictly and decided to follow a mediating path with the law breakers to amend their effect as best he could. Having submitted to appeasement once, perhaps he was in Soapy’s power.[6]

On November 3, 1898, while awaiting the final results of his trial, a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle had Taylor's likeness published (see top picture). On December 10, 1898, Taylor was acquitted of

negligence. Evidence of his wrongdoing as a lawman was ample, but none of it was evidenced

in court.[7] Though acquitted of

negligence, Taylor’s career as a lawman was over. His name was now manacled to

the legendary Soapy Smith, and no key could unlock it.

Once able to leave Skagway, Taylor took his wife, Maud Ellen Stewart, and their five young children, including Stephen Alaska "Lou" Taylor, born in Skagway on May, 13, 1898, back to Idaho. In 1900, with the help of family member Pleasant John Taylor and an older brother or cousin, who was a "showman" and “movey projectionist,” Sylvester became manager of the show. In 1910 his occupation was still listed as “showman, vaudeville and movey projectionist." In 1919 Taylor's occupation is listed as working at the Isis Theater in Idaho.

In the following from a Texas newspaper article from August 1922, Sylvester reminisces his early days in Texas, which includes a strong link to a career in law enforcement, considering his three older brothers were Texas Rangers.

Early settlers will remember the three brothers of this family, who were Texas Rangers, known from border to border of the state of Texas as Ham [Hannibal Giddings Taylor], Eph [Ephraim Kelly Taylor] and Pleas [Pleasant John Taylor] (Doctor Stephen Slade Taylor’s sons). They lived in the days of Indians, and became Rangers to protect their homes, according to Sylvester Slade Taylor, of Reno, Nevada, who is in Fort Worth, visiting his son, S. J. Taylor, 1312 College Avenue. This is the second visit to Texas in thirty-five (35) years and the first time he had seen his sister, Mrs. Sarah Susan Taylor Click for thirty (30) years.

"I went back home and went swimmin’ in the old swimming’ hole, in the nature way,’ the Texan said. ‘But the most exciting of the whole trip was when we went out to the Hart Ranch and saw a oil well brought in. They seem to bring ‘em in while you wait out there. It was the first one I’ve ever seen brought in and believe me it was some sight to these old Nevada eyes." He recounted many interesting things about the early days and the Indian raids. Remember the killing of the elder Dalton, father of Robert Dalton, owner of the Dalton Oil Tract. He saw his first train in Fort Worth, Texas.[8]

In 1930, at age 63, Taylor is listed as a cigar salesman in Reno, Nevada. At age 73 in 1940 he is listed as an attendant at a local college in Spokane, Washington. Eighteen years later, on May 12, 1958, Sylvester Slade "Vess" Taylor passed away at age 91.

At the time I published Alias Soapy Smith in 2009 I depended on the Taylor family tree on Ancestry.com complete with the inevitable mistakes that come with creating such a tree, for the pre and post-Skagway history of Sylvester Taylor. Thus, I was made to believe that Taylor "died comparatively young, though, in 1916 at age 49.” Since then, the information found on Ancestry.com has been updated and his actual death date, as shown in the death certificate below, is May 12, 1958, in Portland, Oregon.[9]

NOTES:

- US v. Sylvester S. Taylor. Whiting wrote that Taylor was found "with a baby on each knee, for protection and also, sympathy."

- Distant Justice: Policing the Alaskan Frontier, by William Hunt, 1987, p. 64.

- Daily Alaskan 07/15/1898, p. 1.

- Skaguay News, 07/15/1898.

- Criminal case 1028-US v. Sylvester S. Taylor. Record Group 21 – US District Courts. Box 16 – 01/01/05 (2). National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Alaska Region, Anchorage, Alaska.

- Gold Fever: A Narrative of the Great Klondike Gold Rush, 1897-1899, by R. M. Dickey, Ed, Art Petersen, Klondike Research. pp. 84-85.

- Distant Justice: Policing the Alaskan Frontier, by William Hunt, 1987, p. 65.

- 1880, 1900, 1910 US Census, Taylor/Holloway Family Tree, accessed through Ancestry.com.

- 1880, 1900, 1910 US Census, Taylor/Holloway Family Tree, accessed through Ancestry.com.

Sylvester Slade Taylor

Dec 24, 2010

Mar 23, 2014

Aug 13, 2017

Aug 18, 2017

Aug 24, 2017

Jan 14, 2020

Taylor, Sylvester S.: pages 508-12, 520, 527, 562, 575-78, 580-81.

"The Reverand Porter was fascinated with the game and firm in his belief that he could pick out the shell under which nestled the little black ball, but when the shell was lifted up the little black ball had mysteriously disappeared, as had also $52 of his hard earned wealth."

—Boulder Daily Camera, June 29, 1893